And their image wasn’t the slightest bit tarnished by their close familial ties with Yamaha’s production racers. Not for nothing were Yamaha’s road twins appended by the prefix RD, meaning race developed.

The RD series replaced the 250cc YDS7 and 350cc YR5 and came with a much tidier engine layout using horizontally split cases, mainshaft mounted clutch and, for the first time, reed valve induction.

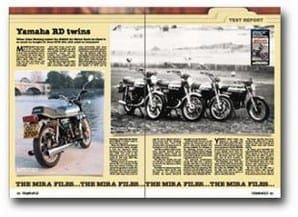

My own flirtation with them started after I’d tested the first reed valve RD250 to arrive in the UK for ‘Motor Cycle’. It flew through the MIRA timing lights at a mean two-way top speed of 93.8mph back in the August of 1973, and its handling, confirmed by the 10mph faster RD350 I’d tested earlier in the month, was a treat.

When the RD250 had finished its demonstrator duties I bought it from the importers Mitsui Machinery Sales for what I recall was £500 and used it the following season for production racing at club level. (RYN 50L, where are you now?)

Nothing serious of course; all I did was fit a set of Dunlop TT100 tyres and rear-set footrests and convert the gearbox to enable the full six speeds to be used. (I can’t remember why Yamaha blanked off the sixth ratio, but it was an easy fix and it clipped almost a half second from the standing quarter mile time – from 15.55 seconds with a terminal speed of 81.0mph to 15.15s at 85mph.

The bike would be ridden to the track (usually Brands) where registration plates would be replaced with number plates and the lights taped up.

The bike was reliable, fun and I’ve still got a couple of trophies to show for the experience. What innocence.

But while I’ve always been keen on Yamaha’s twins, all the way through to the watercooled models, the earlier aircooled examples are my favourites.

At ‘Motor Cycle’ of course, I could indulge my enthusiasm and was able to taste every example that became available. For example, in the following January of 1973, Padgetts of Batley started offering race-style fairing, tank and seat kits along with footrests and provided a tweaked 250 for test.

The improved aerodynamics turned the bike into a genuine ton-plus 250 with a top speed of 100.29mph, despite a front wheel vibration that was unnerving. Not bad when a Ducati 750GT vee-twin I tested a few weeks later tripped the lights at just 109mph flat out.

Six speed gearboxes

Yamaha didn’t make any changes to the 250cc and 350cc twins until 1975 when they were offered with proper six-speed gearboxes. But the RD350B we tested in June of that year was in fact slightly slower than the original. Its mean top speed was just 102.6mph and the quarter mile time of 14.75 seconds at 88.5mph was 0.3 seconds down.

The following year, 1976, was when Yamaha introduced the first of what was to become the best of the series, the RD400C. This, like the 250, came with the ‘coffin’ styled fuel tank and an option of wire or cast-alloy wheels.

The larger capacity came from stroking the 350cc (64 x 54mm) engine to 398cc (64 x 62mm) and using 28mm carbs with revised jetting.

On paper, and especially the important MIRA test data, the 400 didn’t appear to be much more potent than the 350cc model it replaced. In the May 1976 test, the mean top speed of OGT 370P was 103.29mph while the mean quarter mile performance was 14.8 seconds at 89.61mph.

On the road, the bike was a different matter, with enough poke from low revs to lift the front wheel under power without the slightest effort from the rider. It was dynamite, and brilliant fun to ride. In contrast, the RD250C tested the following month was slower than its predecessor at 90.52mph flat out and 15.95s through the quarter mile. Performance declined further with the RD250D tested in May 1977. This model, although slightly faster flat out at 91.8mph, could do no better than 16.4 seconds and 79.4mph through the quarter. In comparison my original model of four years earlier was a rocket.

Redemption was provided in 1978 when Yamaha introduced a number of changes with the RD400E. Both the engine and chassis were improved. The two stroke twin had CDI ignition, revised porting, longer inlet tracts and larger diameter exhaust pipes, the combined effects of which were to raise the claimed peak power to 44bhp at 8000rpm.

Handling was improved with larger diameter 35mm (up from 34mm) fork legs, lighter cast-alloy wheels, while cornering clearance was increased by the mounting of the footrests on plates above the exhaust pipes rather than on an assembly beneath them.

The potent one-piece brake calipers were replaced with floating single-piston units, not so much for more stopping power (which they couldn’t offer) but for reliability, because the originals were prone to corrosion that was difficult to correct.

RD400E

In July 1978, the RD400E zipped through the timing lights at MIRA to become the fastest-ever 400 at 106.64mph and blitzed through the standing quarter mile at 14.3 seconds with a terminal speed of 93.3mph.

None of the mid-range of the first 400 had been lost. It would rise to the occasion just by flicking the grip in the lower gears and was a smooth high-speed cruiser with its rubber-mounted engine keeping the vibes at bay.

This was mitigated by the fuel consumption that dropped to 30mpg at times (misers, of course, could have the four stroke XS400 twin). I liked the riding position but the rear suspension was hard and the brakes were too easy to lock up at low speeds, a legacy of the more spongy floating calipers.

This wasn’t helped the following year in 1979 when the F models were introduced with revised graphics and longer, dog-leg levers. I have a painful memory of locking up the front wheel on a slippery Tottenham Court Road in London and unceremoniously dumping the bike down the road, fortunately without much damage.

With the new decade, Yamaha’s aircooled twins were under siege in the US where exhaust emission regulations effectively outlawed two stroke road bikes. But the RD400G lived on in Europe in 1980 with cosmetic changes (no equivalent 250 was offered), soon to be replaced by the Europe-only watercooled RD250LC and RD350LC twins, opening up a new era in development.

For elegant simplicity, the aircooled twins were, and their survivors still are, a pinnacle of design that surpassed in performance and style anything the opposition could serve up.