The chance to ride certain machines doesn’t come up very often. Some are pampered restorations but some are just plain rare. And when the owner tells you he doesn’t mind you getting the bike dirty and then points you to a prime piece of unfettered trail bike territory it’d be churlish to pass up the opportunity.

Now, trail bike riding was already a huge pastime in the USA before the Japanese really established themselves, but with their typical thoroughness they looked at what was then on offer and produced a bike for just about any off-road application a rider might care to consider.

Suzuki showed considerable prowess, flair and engineering ability with their early bikes and this was demonstrated perfectly with their off-road machinery. Just like many of their competitors the initial trail bikes were little more than standard road machinery that was modified to run on the rough. A typical example was the adaptation of the road-going B105 that was metamorphosed into the B105P. In order to provide lower gearing for off-road use Suzuki, along with their compatriots, offered the choice of two different sized rear sprockets and short length of extra drive chain. The idea was that the owner would ride to the trail on standard road gearing then insert the short length of chain that allowed him to utilise the bigger rear sprocket. After a fun day on the dirt the procedure was reversed and he rode home wearing a big grin from a grand day out.

Suzuki showed considerable prowess, flair and engineering ability with their early bikes and this was demonstrated perfectly with their off-road machinery. Just like many of their competitors the initial trail bikes were little more than standard road machinery that was modified to run on the rough. A typical example was the adaptation of the road-going B105 that was metamorphosed into the B105P. In order to provide lower gearing for off-road use Suzuki, along with their compatriots, offered the choice of two different sized rear sprockets and short length of extra drive chain. The idea was that the owner would ride to the trail on standard road gearing then insert the short length of chain that allowed him to utilise the bigger rear sprocket. After a fun day on the dirt the procedure was reversed and he rode home wearing a big grin from a grand day out.

Of course there were actually a few negatives about all of this; the rider got oily hands in the middle of nowhere that he couldn’t clean, the chain in the off-road mode was compromised by two joints and two split links and there was the small engineering issue of manifestly running the final drive chain purposely out of line. Obviously this was a poor compromise and things needed to change if the bikes were to seriously offer dual-purpose capabilities.

With typical Japanese ingenuity the Suzuki engineers came up with the dual range gearbox system. This was achieved by combining a two-speed drive assembly outboard of the standard box and by careful selection of the two ‘transfer’ gear ratios the factory gave the rider gears for pretty much any situation he was ever likely to encounter. Although the cynic might argue this was little more than a high tech compromise it proved to be both surprisingly robust and hugely popular. The latter is evident by Suzuki’s use of the dual range system across a fair number of their contemporary bikes.

With typical Japanese ingenuity the Suzuki engineers came up with the dual range gearbox system. This was achieved by combining a two-speed drive assembly outboard of the standard box and by careful selection of the two ‘transfer’ gear ratios the factory gave the rider gears for pretty much any situation he was ever likely to encounter. Although the cynic might argue this was little more than a high tech compromise it proved to be both surprisingly robust and hugely popular. The latter is evident by Suzuki’s use of the dual range system across a fair number of their contemporary bikes.

Initially pioneered on the KT120 and TC120 the system was also found on the TC90, TC100, TC125 and TC185. It’s said that the only official application of the technology on UK bikes was on the now extremely rare TC120, which came into the country in fairly small numbers.

Suzuki’s UK import policies in the early period were known to be a little haphazard on occasion and this may account for why Chris originally had a bike that according to records shouldn’t actually have been here. Evidence is fairly sketchy as to when and why Suzuki dropped the novel system but certainly it only ever appeared here on the TC90 and TC120 in the very early 1970s.

In all likelihood the main reason for the cessation of the dual range boxes was one of cost versus sales volume. To produce what was effectively two sets of transmissions on one bike must have been financially punitive and when you factor in the use of cross-drilled drive shafts, ball bearings, springs and push rods assembly costs were almost certainly higher than Suzuki would have wished. With the gradual move to the now ubiquitous selector fork and drum gearboxes Suzuki simply moved on. Another factor was that the company was moving towards bigger bikes in general. With a better understanding of two-stroke technology this allowed them to get more power and torque from their engines and this in turn negated the need for the extra gears. History shows us that the Japanese companies producing two-stroke trail bikes had mastered drum selector five or six speed boxes by 1972/73 and the days of the dual-ratio box were numbered.

In all likelihood the main reason for the cessation of the dual range boxes was one of cost versus sales volume. To produce what was effectively two sets of transmissions on one bike must have been financially punitive and when you factor in the use of cross-drilled drive shafts, ball bearings, springs and push rods assembly costs were almost certainly higher than Suzuki would have wished. With the gradual move to the now ubiquitous selector fork and drum gearboxes Suzuki simply moved on. Another factor was that the company was moving towards bigger bikes in general. With a better understanding of two-stroke technology this allowed them to get more power and torque from their engines and this in turn negated the need for the extra gears. History shows us that the Japanese companies producing two-stroke trail bikes had mastered drum selector five or six speed boxes by 1972/73 and the days of the dual-ratio box were numbered.

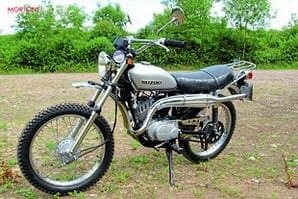

The TC90J was a ground up design of a trail-bike-in-miniature and it was little gem. Suzuki were never afraid to use colour for dramatic effect and many aficionados would argue Suzuki’s stylists were at the top of their game at this period. With colour options running through Ascot red, Monterrey green, yellow, orange or silver (as per Chris’ bike) the company made the maximum visual statement with the diminutive machine.

The Japanese were among the first to understand and acknowledge that to achieve high sales volumes and precipitate the phenomena known as brand loyalty you built small bikes up to a quality not down to a price. Using the same component suppliers as they did with machines such as the 500cc Titan/Cobra Suzuki availed the TC90’s original owners with a quality piece of kit. Using corporate family identity the firm applied the same level of quality fittings to the little bike from the speedo right through to the rear light. Chrome guards at both ends protected rider and machine from the worst of the dirt while a surprisingly efficient suspension system takes care of the majority of bumps and humps but more on this later.

The Japanese were among the first to understand and acknowledge that to achieve high sales volumes and precipitate the phenomena known as brand loyalty you built small bikes up to a quality not down to a price. Using the same component suppliers as they did with machines such as the 500cc Titan/Cobra Suzuki availed the TC90’s original owners with a quality piece of kit. Using corporate family identity the firm applied the same level of quality fittings to the little bike from the speedo right through to the rear light. Chrome guards at both ends protected rider and machine from the worst of the dirt while a surprisingly efficient suspension system takes care of the majority of bumps and humps but more on this later.

Bearing in mind the bike was inevitably aimed at younger first time riders to whom appearances were pivotal and this is probably why the bike sports a chrome high-level exhaust system, along with the minimalist but effective heat guard.

Ditto the small chrome chain guard, which could so easily have been painted satin black. Doubtless this added to the cost but when you’re a teenager shiny parts are a natural lure for your, or more likely your parents’, money.

Rider comfort seems to have been high on Suzuki’s list of priorities and the seat is amazingly luxurious for such a small capacity machine. Add in a competent pair of mirrors and thoughtful detailing such as rubber covers to the ends of the control levers and it’s blatantly evident that Suzuki viewed this tiny sub-sector of their market with nothing but seriousness.

All of this would have been for nothing if the engine wasn’t any good but again the R&D team at Suzuki Central produced a fantastic motor. As previously detailed in CMM on numerous occasions, these miniature disc valve induction two-stroke motors are amazingly strong, reliable and dependable little tykes. Eschewing what was fast becoming the norm for square or over square engine configurations Suzuki opted for a comparatively long stroke motor. This is key to the driveability that owners enjoy and champion. Although it is entirely possible to rev the bike it doesn’t need a heavy hand to make good progress and that slightly under square architecture facilitates a little more grunt than the uninitiated might expect.

All of this would have been for nothing if the engine wasn’t any good but again the R&D team at Suzuki Central produced a fantastic motor. As previously detailed in CMM on numerous occasions, these miniature disc valve induction two-stroke motors are amazingly strong, reliable and dependable little tykes. Eschewing what was fast becoming the norm for square or over square engine configurations Suzuki opted for a comparatively long stroke motor. This is key to the driveability that owners enjoy and champion. Although it is entirely possible to rev the bike it doesn’t need a heavy hand to make good progress and that slightly under square architecture facilitates a little more grunt than the uninitiated might expect.

Although by their very nature disc valve motors tend to be physically wider than a piston ported unit the TC90J is commendably narrow and even in hard off-road use it’d be difficult to blame the engine’s width for any get-offs or collisions. With space always at a premium on small bikes the designers chose to fit in a fairly capacious air box behind the barrel where a carburettor might live on a more orthodox stroker; its positioning also allowed serious off-roaders easy access when servicing demanded the cleaning out of many hours of inhaled dirt and dust. Obviously a dual-range box system must add to the engine’s size but on a 90cc motor it’s hardly obvious or a burden.

Looking at the left-hand side of the motor there’s a large alloy blister that contains the dual-speed mechanism and the requisite selector device. Rather than choose to use a small, unobtrusive, zinc plated lever with a subtle knob on the end Suzuki’s engineers went all out to make a visual statement. Looking more like a control device from a Victorian locomotive the large chrome T-handle is where everyone can see; it’s exactly the sort of thing that obliges the unknowing to ask that perennial question “what’s that for then mate?”

Riding the TC is so much fun you begin to ask yourself if it’s this good how come some government department hasn’t either legislated against such enjoyment or found a way to tax it? From the moment the motor fires up you just know the bike is going to deliver the goods along with loads of fun. The engine is whisper quiet with none of the cold engine piston slap you can get with some strokers as they gradually warm up. The choke can be taken off pretty much as soon as the engine is running and then you get to listen to the exhaust note; if the motor is quiet the exhaust makes up for the lack of decibels. Although by no means anti-social the little TC90 makes its presence felt with a typical two-stroke crackle that informs anyone nearby that the machine means business. While we were riding during the test a few dog walkers and ramblers walked by but there was nary a complaint or shaken fist so perhaps it’s the exhaust note rather than the actual noise level that’s so characteristic.

Riding the bike is so easy it’s very tempting to call it child’s play. The motor carburates beautifully and there’s never a moment’s hesitation when rolling the throttle on or off. Despite having only relatively small flywheels there’s a good reserve of instant pick up and in the absence of any other mechanical or physical phenomenon it must, once again, come back to that longer stroke set up. Phrases such as small, poised and beautifully balanced have, in the past, been overworked into clichés by journalists but in the case of the little Suzuki there were never truer words written; the TC90 is dangerously close to small trail bike perfection – especially so given its age.

Riding the bike is so easy it’s very tempting to call it child’s play. The motor carburates beautifully and there’s never a moment’s hesitation when rolling the throttle on or off. Despite having only relatively small flywheels there’s a good reserve of instant pick up and in the absence of any other mechanical or physical phenomenon it must, once again, come back to that longer stroke set up. Phrases such as small, poised and beautifully balanced have, in the past, been overworked into clichés by journalists but in the case of the little Suzuki there were never truer words written; the TC90 is dangerously close to small trail bike perfection – especially so given its age.

If you had to find an issue, and it would be unfair to call it a problem, the pedant might argue the rear shocks are limited but then again they were never really intended for gentlemen of a certain age and increasing girth (and I firmly include myself in this category). Running the bike in the high (or road ratios) on the rough gravel track shows just how easy going the Suzuki’s handling is but drop it into neutral, select low ratio, run the bike again and it’s little short of breathtaking. Obviously by opting for what amounts to a much smaller front sprocket any top end performance is wiped out but what you lose on the swings you gain roundabouts as they say. At walking pace or even slower that engine pulls like a miniature steam engine and even quite steep gradients can be taken without any drama or fear of failure. Thrapping the little TC around in low was a great way to waste a day and it’s an experience we’d happily repeat. Again and again… ![]()