When the Suzuki Katana was first shown at the Cologne exhibition in 1980, it was generally dismissed as a styling exercise. Yes, it was stunning, but the Japanese would never produce a bike like that really. Would they?

Yes, they would. A year later the Katana was on the roads. Well, two Katanas were: the GSX1100S and the GSX1000S, which looked identical but the smaller one, being just under 1000cc, made it eligible for production racing of the era.

Flat-slide Mikunis

The only thing that distinguishes a 1000 from the 1100 is the carb set. The 1000 got a set of flat-slide Mikunis which make it, allegedly, a bit quicker. It’s much rarer, though. Almost everyone opted for the extra cubes and the lighter throttle.

Mechanically, the Katana was nothing new. The GSX1100 had been around for a few years. Big, bulky in weight and looks, but it handled coherently and it was about the fastest Japanese bike of the day. The Katana was little more than that excellent 16-valve engine dropped into a café racer chassis. But what a café racer chassis.

In keeping with the technology of the day, it was long – the only way the Japanese knew then to stop their bikes from wobbling like hell was to give them a long wheelbase. It was also quite heavy.

But it looked like nothing else. Insectoid, low, hunched, futuristic, space-age: many manufacturers have tried to provide truly avant-garde styling and most have embarrassed themselves in the process. Remember the Starck-styled Aprilia? The Moto Morini Dart? Well, Suzuki didn’t fall into that trap.

The Katana had people gasping in admiration. It remains one of the truly innovative styling jobs to come from Japan, and its influence can be seen even in today’s machines.

For a start, it had a low, low seat. Many big bikes of the day had a seat that was on much the same level as the top of the fuel tank. Suzuki, with the Katana’s chassis, reasoned that the arse end of the bike could be built lower as it wasn’t holding the tall engine, and that would mean a nice low seat height (all of 30” or about the same as a dinky Moto Guzzi Monza), lower centre of gravity, and so on. Everyone does it that way now.

But the actual styling was the master-stroke. Executed by Hans Muth of Target Design in Germany (the styling house responsible for the BMW R100RS, among other gems), it married a poised droop-snoot frame-mounted fairing with an arrowhead-shaped petrol tank, and detailing achieved by very clever colour co-ordination.

So the rider’s portion of the seat was dark grey/black to match the black bodywork bits like the headlight surround and the black chrome exhausts, and the rest of it silver, to match the overall colour. The front half of the mudguard was silver, and the rear half black. It had the overall effect of slimming the lines.

There were splashes of colour, like the red tank stickers which echoed the orange of the indicators. There were little touches like the dummy switches set into the side panels, which gave it a sort of techno appearance. and the little badge of a katana bisecting a Japanese character. (Oh, a katana is a Japanese samurai sword, if you didn’t know.)

Single instrument binnacle

There were the amazing clocks: a single instrument binnacle which contained twin needles for speedo and rev counter, plus a bank of five warning lights underneath them. People say the needles contra-rotate, but they don’t: they both go clockwise, as normal. It’s just that the speedo needle starts from the four o’clock position and the rev counter needle from ten o’clock, so they appear to counter-rotate as they sweep round.

Aerodynamics played their part. The riding position and the droopy nose fairing were intended to make the airflow pass smoothly over the rider. Of course, this only worked at high speed, but high speed was what the Katana was all about.

Straight out of the crate it was capable of 140 mph, previously the preserve of very few bikes: the Jota had managed it, but not much else. The Honda CB1100R and the Kawasaki GPz1100 which appeared just after the Katana could do similar speeds, but really, 140 was the stuff of dreams back then.

And the Katana did it effortlessly and with huge mid-range grunt. That GSX1100 engine was left mostly unchanged – there was damn all wrong with it and it wasn’t lacking in power. Superior aerodynamics and a very slight power boost from the original GSX1100 were all that was needed to push it past the 140 mark.

An indicated ton came up at a mere 6000 rpm and the redline was at 9000. The Katana was just loafing at that speed. If you opened the throttle the surge was immediate and impressive. It just went on and on and on, and only started to tail off past 125 mph, when it would gather speed rather than accelerate. If you were to ride a Katana today, you’d still find it a fast bike.

An indicated ton came up at a mere 6000 rpm and the redline was at 9000. The Katana was just loafing at that speed. If you opened the throttle the surge was immediate and impressive. It just went on and on and on, and only started to tail off past 125 mph, when it would gather speed rather than accelerate. If you were to ride a Katana today, you’d still find it a fast bike.

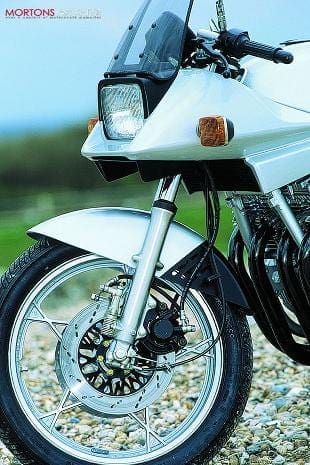

Handling? Very stable, very slow, due mostly to a long wheelbase and the use of a 19” front wheel which was a bit dated even in 1981.

I remember bashing one round Castle Combe and it needed a lot of muscle to get into a bend, but once there it stayed on line like a supertanker that had lost its rudder. Agile it was not, but then I don’t think any 240kg bikes are. Some like it that way, mind.

They did a red and silver model and a maroon and silver one, and a sort of blue-black one. Later ones came with a gloss black engine and wheels styled like those from the XN85 Turbo, but really, for the purists, the original silver ones are the best-looking.

The Katana died early. Kawasaki’s GPZ900R stuffed it as a sports bike and Yamaha’s new FJ1100 settled into the sports-tourer role it was to occupy for over a decade. The last Katanas were sold in early 1985.

What goes wrong

Nothing whatsoever with the engine. It’s as strong as a steam locomotive. The electrical system is early-1980s Suzuki, so pretty crap. Any purchaser should always check that the beast is charging. The hydraulic anti-dive fitted to the front forks is useless in the way of all anti-dive units of the era, which is why we don’t see them around any more.

The finish isn’t the best and Katanas start looking very scrappy very quickly. Black chrome exhausts show corrosion up much worse than the bright chrome ones and the silver frame paint on all models seems to flake off rapidly.

The grey seats manage to accumulate dirt like no other and as they’re covered in a kind of suede that can’t just be wiped clean with a damp cloth: you really need to dig out some car upholstery cleaner and work at them.

Other Katanas

Suzuki also applied the Katana name to other, lesser bikes. A similar styling job was done on the GS550 and shaft-drive GS650, and in the US just about anything that bore a GSX badge was called a Katana. I suppose we ought to mention the 750 – again, watered down, but not as much as some, and with a rather neat pop-up headlight. Then there were the watercooled 250s and 400s, which used exactly the same styling as the originals. Very nice, but grey imports only.

Suzuki did actually build a batch of 1100 Katanas in 2002, as a sort of farewell to the whole Katana concept, but I don’t think any made it out of Japan. ![]()