Hard to believe now perhaps, but Moto Guzzi was for a long time Italy’s numero uno manufacturer of motorcycles. Although the glory has faded over the last decade or two, business was booming in the second half of the Seventies.

The 1975 launch of the Le Mans 850 was probably the secret of Guzzi’s success, even though the bike itself wasn’t vastly different under the skin from any other of the company’s big V-twins.

As is well known, the faithful 90 degree ohv engine first saw the light of day in an extraordinary military three-wheeler, but had been the company’s trademark feature since the first V7 arrived in 1967.

V7s were large, heavy, slow and really not very promising. The magic Italian ingredients of speed and style only arrived with the Sport version announced in 1972. By tuning the engine to produce 125 mph performance and arranging for the frame tubes instead of the generator to occupy the space between the cylinders, chief designer Lino Tonti turned a motorcycling sow’s ear into a silk purse.

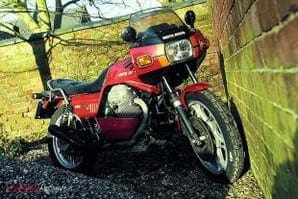

The V7S duly transformed itself into the S3, using a cheapened (chain driven camshaft) version of the 748cc engine. This grew to 844cc for the Le Mans, still rated as one of the best-looking bikes ever by many roadside pundits.

Despite the engine’s old-fashioned design, with a 10.2:1 compression ratio, enormous valves and Dell’Orto ‘pumper’ carbs, it summoned up 80 bhp at 7300 rpm, enough for over 130 mph.

Despite the engine’s old-fashioned design, with a 10.2:1 compression ratio, enormous valves and Dell’Orto ‘pumper’ carbs, it summoned up 80 bhp at 7300 rpm, enough for over 130 mph.

While in most respects the ‘Lemon’ was an S3 with bigger pistons, Guzzi’s touch of genius, in a world of naked bikes, was to attach a small plastic flyscreen to the front end, making their sportster instantly recognisable from any angle. And before anyone writes in about the Royal Enfield Continental GT, no, this wasn’t an entirely new idea!

Apart from style and performance, the Le Mans also boasted handling reckoned to be superior to the Japanese competition. Admittedly, that wasn’t saying very much in 1976, when Honda CB750s, Suzuki GT750s, Kawasaki Z900s and the rest were wont to wobble into oblivion at the least excuse. There’s no doubt that Guzzi’s straight-tube frame, with bolt-on lower rails for easy engine removal, was a masterpiece, holding everything in line and cleverly keeping the bike low.

Suspension that offered slightly less compliance than concrete, stopped all the unnecessary ups and downs that blighted overweight Japanese fours. It also did much to reduce some of the undesirable side-effects of the shaft drive.

Transferred weight

Another important factor was the crouched riding position provided by low clip-on handlebars which transferred weight forwards and improved the aerodynamics: very different from the fashionable ‘sit up and beg’ pose produced by American-influenced high, wide handlebars.

Some traditional Italian weaknesses remained. The paint, for instance, was poor in places, although some people didn’t realise that most of the black wasn’t supposed to be glossy! Meanwhile, the upswept exhausts were finished in a light dusting of heatproof black that needed respraying after every wet journey.

Other cosmetic defects included impossible-to-clean cast wheels and a foam rubber seat, which looked marvellous until someone actually sat on it. The only time you saw a Le Mans that didn’t have a split seat was in a showroom.

Other cosmetic defects included impossible-to-clean cast wheels and a foam rubber seat, which looked marvellous until someone actually sat on it. The only time you saw a Le Mans that didn’t have a split seat was in a showroom.

And the Brembo disc brakes that turned bright red with rust overnight? “Oh, they’re supposed to do that, sir. Cast iron, you know – the only way to make ‘em work in the rain…”

The rust was wiped off as soon as the wheels turned but you were stuck with Guzzi’s patented linked brakes. One front disc was operated by the handlebar lever as normal, while the other was plumbed into the foot pedal hydraulics in such a way that about three-quarters of the pressure went to the front caliper.

Helped by a memorable series of ads in the motorcycling press (‘Long-Legged and Easy to Live With’) which featured a bevy of scantily-clad females, the success of the Le Mans had a knock-on effect on the rest of the range.

In the second half of the Seventies, Guzzi V-twins, big and small, were a common sight on the roads. It’s a sad fact that they were a less common sight in the Eighties and virtually invisible thereafter. What went wrong? Plenty, but the Le Mans Mk2, launched in 1978, might have been one of Guzzi’s first mistakes.

Cement footwear

Before the Mandello del Lario mafia turn up with their Black & Deckers and custom-fitting cement footwear, let me say that the Mk2 wasn’t really a bad motorcycle. In some ways it was better than the Mk1. Unfortunately, most of the ways in which it was better took the bike away from its role as the fastest, sportiest, most stylish two-wheeler on the market.

Having given us the bikini fairing, Guzzi equipped the Mk2 with the large expanse of plastic found on the Spada tourer – rotating upper half and lowers that wrapped around cylinders and exhausts – all designed for aerodynamic efficiency, we were assured.

As the firm’s facilities included a wind tunnel (where the V8 racer had been sculpted), no-one really doubted the claim. It was just that no-one really wanted a touring fairing on a sports bike.

Nothing much had changed mechanically, so in a way the Mk2 offered the worst of both worlds. Uglier, slower and heavier than a Mk1; more uncomfortable and impractical than a Spada tourer – and probably slower on most roads because it didn’t have the 950 engine’s torque.

Nothing much had changed mechanically, so in a way the Mk2 offered the worst of both worlds. Uglier, slower and heavier than a Mk1; more uncomfortable and impractical than a Spada tourer – and probably slower on most roads because it didn’t have the 950 engine’s torque.

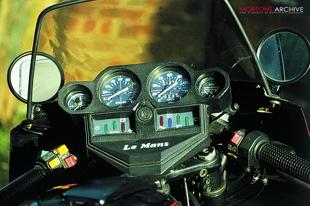

So, unless you were impressed by a large collection of wobbly Veglia instruments, the number of genuine improvements could be counted on the fingers of one hand (even after that visit from the mafia). Better seat, more stable centre stand and a bigger battery. (Less pathetically small battery is more to the point.)

Meanwhile, the Japanese had been busy, resulting in a host of new superbikes that went faster than the Le Mans and broke down less often. Italian ‘character’ just wasn’t enough when faced with a choice between a pushrod V-twin and a six cylinder Honda CBX, Yamaha XS1100, Suzuki GS1000 or Kawasaki Z1300.

Now we are in the classic afterlife, with a completely different outlook. Although Le Mans prices have never matched those of SS Ducatis of similar vintage, the Mk1 always held its value.

The contrast between a Le Mans (of any model) and its Japanese opposition is startling. While the Guzzi initially seems about half the size of the big fours and sixes from the East, it’s actually almost as long but much lower and generally narrower. Even across the vee of the cylinders, the engine is relatively compact.

Shudder and wheeze

The differences become even more pronounced during the ride. With an almighty shudder and wheeze, the big twin fires (or sometimes not, particularly in the Mk1’s case, whose battery had a hard task coping with 10.2:1 compression pistons), making a subdued rumble.

Despite those huge flywheels, a blip of throttle quickly produces plenty of revs… and noise! The main source is the open intakes rather than the exhaust, which is very quiet when wearing standard silencers. Although not as quiet as the original Lanfranconis, the test Mk2’s pipes still sounded relatively hushed.

Other obvious departures from standard included the seat and enormous grab rail, which wasn’t exactly pretty but would have been useful for any pillionists braving the rear quarters.

As a former Lemon owner, it didn’t take long to re-programme my brain to cope with the Guzzi’s idiosyncrasies. The slow, long-travel gearchange that habitually serves up false neutrals at embarrassing moments, is probably the worst feature. Don’t change mid-way through a corner or during an overtaking manoeuvre is the rule.

Then there’s torque reaction. At a standstill, sudden changes of engine speed threaten to pitch the machine on its side. It’s less noticeable once you’re moving but you can never quite forget that the crankshaft is in line with the wheels. Don’t close the throttle going into bends is therefore the second lesson. Still, you’re not supposed to do that, are you?

Then there’s torque reaction. At a standstill, sudden changes of engine speed threaten to pitch the machine on its side. It’s less noticeable once you’re moving but you can never quite forget that the crankshaft is in line with the wheels. Don’t close the throttle going into bends is therefore the second lesson. Still, you’re not supposed to do that, are you?

The other sort of torque reaction comes free of charge with shaft drive. In this case stiff suspension disguises the ‘jacking’ effect at the rear end, as famously suffered by BMWs of the era. Of more significance in general Guzzi riding, I think, is the amount of unsprung weight in the shaft and gear housing, which affects the suspension’s ability to absorb bumps.

As the springs at both ends are rock-hard to start with, the Le Mans isn’t happy on rough roads. That’s an understatement, actually. When I ran a Mk1, the main speed limiter was the suspension. On some surfaces you took such a battering that it was difficult to see where you were going, never mind stay in the seat or operate the controls smoothly.

Eventually I learned to stick to smooth, sweeping A-roads whenever possible. No need to change gear. Just wind it up past 5000 rpm, when the asthmatic intake wheezing changes to a crisp roar, and lean on the high-speed breeze.

Unfortunately for those who like old-style bikes, the Mk2’s fairing means that the only breeze hits the top of your head. Meanwhile, the extra weight saps the power. Worse still, on slow backlanes the plastic thuds and shakes as the engine accelerates from low revs, while the steering feels anything but nimble.

Above about 60 mph everything starts to fall into place (yes, even your knees), and the Mk2 turns into a capable sports tourer. Fine, but if you want that, why not just buy a Spada with a comfortable seat and soft suspension? Surely the whole point of the Le Mans was to deliver the basic, flies-in-the-toupee motorcycling experience?

Guzzi lost the plot even more with succeeding versions. The Mk3 was probably more durable but wasn’t improved by the new square-look cylinders. 1984’s Mk4 was a bit of a disaster, simply because 16-inch wheels didn’t work properly in a chassis designed for 18-inchers.

The Mk5 reverted to the original wheel size and ethos but by 1987 the Le Mans was hopelessly outdated in general engineering. Only Harley can get away with that.

While some hope was offered by the heavily-revised Daytona 1000, with trick swinging arm and high-tech cylinder heads, Guzzis were out in the wilderness by this stage, outclassed by Japanese sportsters.

What they should have done in 1978, I reckon, was to leave the Le Mans with its bikini fairing and concentrate on improving the gearbox, suspension and finish. Using the 950 engine (as in America) would also have been an obvious step forward.

But they didn’t, which meant that the original was really the best. ![]()