When Ben Inamura and his team gave the world the Z1 it was a spectacular delivery. If you remember that period of the 70s, the very sight of a Z1 was like a punch between the eyes by George Foreman. The world of biking had changed overnight. Well it did if you were in the market for a big bore road burner.

If you wanted something on similar technological plane, without the inbuilt death wish, there really wasn’t too much choice; nothing really outstanding was on offer. The British bike industry was offering same old same old, Honda was trying to tempt you with year-on-year revisions of the 500/550/750 sohc four concept, Suzuki were girding their loins for the launch of the GS750 and good old Yamaha were still punting out the XS650 series Japanese Bonnevilles.

Dear biking world, please find enclosed another punch between the eyes, kind regards Ben Inamura and colleagues. This time Sugar Ray Leonard had just given the complacent upper middleweight biking world a jolly good slap.

At first glance it was a brave move of Kawasaki to opt for a capacity that was (psychologically at least) mired in mental pictures of vibratory twins, oil leaks and failing electrics from the Prince of Darkness, good old Joe Lucas.

At first glance it was a brave move of Kawasaki to opt for a capacity that was (psychologically at least) mired in mental pictures of vibratory twins, oil leaks and failing electrics from the Prince of Darkness, good old Joe Lucas.

At second glance, and with the benefit of hindsight, the logic was obvious and clinically cold. Take a capacity that no one else wants to bother with, give a design brief to your best guys and ask them to make an upper middleweight bike that will blow everything else away. Add in the lessons learnt since the inception of the Z1 and it’s hard to see how you could possibly get it too wrong.

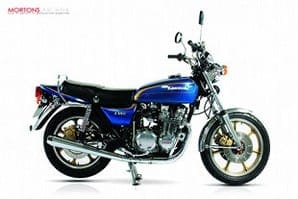

Looking like a smaller version of the big Z (even though it was complete redesign), the Z650 just looked right from the start, even down to the 4-2 exhaust system. Fitted with a plain bearing bottom end, as opposed to rollers a la Z1, and a chain primary drive, rather than big brother’s gear driven powered train, the 652cc motor produced a claimed 64hp.

Another upgrade from the Z1 was the position of the shims for valve adjustment. On the Z1 they were easy to get at on top of the cam bucket, on the Z650 they were underneath. The cons were less accessibility and more hassle; the pros were fewer adjustments necessary and the likelihood of the cam spitting out a shim was four fifths of nine tenths of buggar all (an internationally recognised unit of engineering probability).

Another upgrade from the Z1 was the position of the shims for valve adjustment. On the Z1 they were easy to get at on top of the cam bucket, on the Z650 they were underneath. The cons were less accessibility and more hassle; the pros were fewer adjustments necessary and the likelihood of the cam spitting out a shim was four fifths of nine tenths of buggar all (an internationally recognised unit of engineering probability).

Perhaps more importantly the lack of mass and the five years’ experience of getting the 900s to handle meant the Z650 was, comparatively, glued to the road. In modern terms there’s undoubtedly room for vast improvement with any Z650’s handling but back in 1976 it really was the knees of the bees.

Rather understated

In aesthetic terms, the Z650 was always rather understated; even when compared to its bigger siblings. For some this was not a problem, for others the appearance seemed to suggest a certain blandness, which really wasn’t the case. As is the way of such things, the Z650 received an array of improvements and modifications over its lifetime; most to the good, although the SR version is an acquired taste.

The subject of this month’s feature is a Z650C3 and as such is tacitly recognised within the UK as possibly the iconic Z650. Perversely the existence of the C1 and C2 models doesn’t seem to appear in official literature. Interestingly, it was the silver C2 model that appeared in countless road tests of the time and of which contemporary journalists wrote so highly.

The C3 had the benefit of alloy wheels, first seen on the apparently non-existent C1, along with sintered metal brake pads, in an attempt to impart some retardation in damp and misty little old Europe. However, for many it was the paint and graphics that really flicked their switches. With swooping gold coach lines and decals against a blue background running from the headstock to the tail-lamp this one simple act raised the bike’s visual profile way above its predecessors. Although the C1 and C2 had bolder graphics than the B series it’s the C3 model that is generally acknowledged as commanding the interest and money.

The C3 had the benefit of alloy wheels, first seen on the apparently non-existent C1, along with sintered metal brake pads, in an attempt to impart some retardation in damp and misty little old Europe. However, for many it was the paint and graphics that really flicked their switches. With swooping gold coach lines and decals against a blue background running from the headstock to the tail-lamp this one simple act raised the bike’s visual profile way above its predecessors. Although the C1 and C2 had bolder graphics than the B series it’s the C3 model that is generally acknowledged as commanding the interest and money.

In an effort to add spice to our undoubtedly dull lives those awfully nice chaps at Kawasaki invented a system of bike nomenclature that defies belief. For reasons lost in the mists of time the C series of models are colloquially known as ‘Custom’ models, even though they aren’t! It’s possible that this may have something to do with the cast alloy wheels but this is pure speculation. The next series are the D models, which are Custom models, with 16in rear wheels etc but these are badged as SR, which may stand for Stateside Replica.

What to buy

What to buy

With a model run from 1976 through to the final 1984 F series (or H series in the USA) there’s a fair array of models and guises to choose from. In all honesty it really is down to personal preferences as much as anything else. There is little doubt that the early models with a single disc really did need the later twin disc set up and you may well decide to upgrade the earlier model’s front end if this is where your interests lie.

The Z650 is one of those bikes that seems to attract considered modifications from loving owners, so be prepared to view non-standard bikes with aftermarket swingarms and pod or K&N type filters. Ask if the bike is standard before travelling any distance if originality is your thing. The bike is often upgraded with a 750 conversion, USD forks and mono shock rear end just to keep this seminal UJM in competition with modern bikes. Sacrilege or common sense? That’s a call you’ll have to make, but it’s a real shame to destroy a pristine C model; much better to keep one of them for Sunday best and buy a ratter to turn into a street sleeper.

What goes wrong

Love or loathe them you can’t knock the Z650, it’s a tough old bird that’s hard to kill unless oil changes have been neglected. In this case the plain bearings will have taken a hammering. Bottom end noises on start up aren’t unknown but unless significant can be generally disregarded.

Unsynchronised carbs will exacerbate any problems lurking in the bowels so try a quick balancing to see if it helps. Tinware, trim and standard exhausts are rarer than turtle fur so don’t make rash assumptions if buying a project. The C series have a novel rear caliper mounting bracket that also doubles as one half of the rear caliper. An overhaul necessitates removal of the rear wheel.

Early models have a single row camchain which can wear quickly. Replacement requires a crankcase split, but the head and barrels can remain undisturbed if you remove the cams and split the big end caps to lift out the crank. Later models have a hy-vo chain which is much more durable. All versions of the tensioner need constant fettling.

Early models have a single row camchain which can wear quickly. Replacement requires a crankcase split, but the head and barrels can remain undisturbed if you remove the cams and split the big end caps to lift out the crank. Later models have a hy-vo chain which is much more durable. All versions of the tensioner need constant fettling.

Drum braked versions are hassle-free, but the disc fitted to C and D models can suffer from seizure and cracked discs. Servicing the caliper requires removal of the rear wheel, so it frequently gets left until its condition is terminal.

In a similar vein, the rear discs of the C series are prone to cracking. Factory wisdom dictated that the specified pattern of drilled holes would negate harmonic vibration in use. Many would argue that better harmony might be engendered if the damn brake disc didn’t fall apart at that one vital moment!

Last, but by no means least, is the highly entertaining starter clutch, which can die leaving the owner reliant on the kick-starter. Repair of this item is the source of much angst and debate among aficionados of the smaller Z. The purist argues that the only real way to repair is to split the cases while the pragmatist argues it’s possible to do the job from the bottom of the engine lying on your back and delving into the bike’s giblets. The former requires a wad of cash, plus muscles to remove the lump from the frame. The latter demands the patience of Buddha and dexterity of an eminent gynaecologist. You make the call, cos I’m not getting involved! ![]()