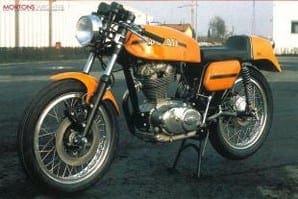

Ducati 350 Desmo

Ducati is rightly famed for its big vee-twins but they owe their success to the smaller range of 'bevel-drive' overhead-camshaft singles ranging in capacity from 125cc to 450cc.

Designed by the legendary engineer Dr Ing Fabio Taglioni, these embodied all the best of Italian flare, providing simplicity and style.

Some were good (such as the 250cc Mach 1) and some, styled for the novel requirements of the US market, were bad. The best combination of power, smoothness and agility was demonstrated by the 350cc version, the first of which was the 'Sebring', made from 1965 in what has become known as the 'narrow-case' version.

Two years later, the first 'wide-case' model with stronger crankcases was offered as the 350cc Mk3, which also came with the option of desmodromic valve operation, a feature that had been employed on Ducati racing machines to enable quicker valve opening than sprung valves.

And so the Desmo legend was enhanced. In 1971 the 'Silver Shotgun' 350cc Desmo was styled along the lines of the first Ducati vee-twins and GP racers with metal flake silver finish.

In 1973, the bike had a complete makeover but Ducati decided tc stop manufacturing the singles. For reasons unconnected with the quality of the machines, only 300 had been sold in the UK in the previous eight years.

The bike pictured is a 350cc Desmo – with a top speed of 105mph and weighing just 285 pounds. It was brought to the UK by Ducati spares specialist Mick Walker and was one of only seven of its type in Britain with the yellow paintwork and disc brake.

As soon as riders were aware of it, demand was such that the remaining machines from the Bologna factory were snapped up.

Laverda SFC750

Motorcycles were just part of the engineering-based business that included the manufacture of combine harvesters run by Piero and Massimo Laverda in Breganze, northern Italy.

But bikes were the brothers' first love and racing them a close second. Soon after the factory (established by their father) had developed a 650cc twin in the late Sixties they developed it into the 750S and entered tuned versions in endurance races.

Experience showed the road machine had its weaknesses when raced but in 1971 chief engineer Luciano Zen designed a production racer – the SFC750 based on the ohc 750 twin. It repaid them by winning the Barcelona 24-hour race.

This was a carefully assembled motorcycle made in very limited numbers for selected customers. It was built for durability rather than outright performance with a braced frame, needle roller swingarm and taper roller steering bearings. The close-ratio five speed engine retained its belt-drive dynamo and starter but had bigger valves, forged pistons and a roller-bearing crankshaft. It was guaranteed to develop 70bhp.

Along with the racing fairing, tank and solo seat it was fully equipped with lights, so some were used on the road, making it a rare, if loud, 130mph sport bike. By 1974, the SFC's drum brakes were replaced by triple discs, a higher compression ratio and bigger Dell'Orto carburettors, while the final Electtronica model of 1975 had a new cylinder head and electronic ignition with a pick-up on the primary drive case.

Only about 550 of the SFCs were made in five years, so prices are mouth watering. Expect to pay £20,000-plus.

Laverda 3CE/Jota

Laverda 3CE/Jota

Once it became apparent that their twins would soon be outpaced, Piero and Massimo Laverda in 1971 investigated the idea of a three-cylinder engine. It had potential but the bike looked ungainly, so a revamp was carried out before the 981cc 3C went into production in 1973.

This was a beaut, having clean symmetrical lines that belied the immense double-overhead camshaft engine's proportions. Although big it wasn't ungainly once on the move because the 3C was slim and the steering in fact lighter than the 750 twin's.

The exhaust sounded unique too with the engine's 180-degree crankpins. Purists will like the massive brakes, wire wheels and large headlamp. The legend that became the Jota started in the UK when, in 1974, importers Slater Brothers modified the engine with perkier cams and less restrictive – and fruitier – exhaust, calling the machine the 3CE. It had a genuine top speed of 135mph, making it the fastest production motorcycle available.

These changes were incorporated into the Jota for 1976 which sold for 2195 guineas and it was this machine – featuring disc brakes and cast-alloy wheels – that first topped 140mph in tests at MIRA, creating an image of classic Italian performance that still prevails.

Morini 3½

Morini 3½

An Italian motorcycle doesn't have to be big to be a classic, as the little 350cc Morini vee-twin proved.

For what the family-owned Bologna factory lacked in capacity, it compensated for with innovative design.

Until the mid-Sixties the factory had been famed for its racing exploits since Tarquinio Provini (on a dohc Morini single) nearly beat Honda-4 mounted Jim Redman to the 250cc world title in 1963.

The Three-and-a-half introduced in 1975 was a completely new departure for designer Franco Lambertini who drew up a 72-degree vee with Heron-style cylinder heads, a feature that offered a good spread of torque with low fuel consumption.

In sports form it produced 39bhp and just topped the 100mph mark flat out. But with beautifully finished castings and chassis detailing that included a chunky double sided drum brake it was also a fine handler.

Before the decade was out Morini had been bought by the Cagiva owners and some derivatives of the 350 were made under duress at Ducati. When a US group bought a share in Ducati the Morini rights were sold back to the family-owned Franco Morini concern.

Moto Guzzi Le Mans Mkl

Moto Guzzi Le Mans Mkl

It might have been something in the water, or more specifically the close proximity of Lake Como in northern Italy that injected a romantic flavour into the Moto Guzzis of the late Seventies.

While the factory at Mandello del Lazio had been sticking to its lean and lithe strategy with beautiful bikes like the V7-Sport and 750-S3, it was clear that demand for extra performance was paramount in a world increasingly filling up with four-cylinder Japanese superbikes.

But in a cash-strapped economic environment, Guzzi could take only one route – to stretch the fabled vee-twin's capacity to 850cc.

In so doing the engineers created what I regard as the best of the Guzzi marque, for when the engines became even bigger (subsequent models have reached 1100cc) they became lumpier and more awkward.

The key feature of the Moto Guzzi Le Mans Mkl was the retention of the traditional rounded detailing of the engine and the robust tubular steel frame.

Even the fuel tank was essentially the same.

But subtle changes including a new seat, handlebar fairing and alloy wheels and the Le Mans came to represent the cool style of a Neapolitan lover. A higher top speed of about 125mph resulted from a pair of chunky looking 36mm-choke Dell'Orto carburettors, 10.2 to 1 compression pistons and higher gearing.

Still with a long 59 inch wheelbase, but a low moulded foam seat (that cracks too easily), the Le Mans provided stable handling and, with linked Brembo disc brakes, quite phenomenal stopping power.

The Mkl Le Mans was followed by less stylish and bigger capacity versions up to Mk 5 but the original is still the best to go for. ![]()