Honda’s CB250N twin, the Super Dream, was a remarkable motorcycle. Sold in the UK from 1978, it was a big bike for its capacity and weighed as much the average 650 of the day. With only average power for a 250cc four-stroke, it struggled to reach 90mph flat out. So the Super Dream wasn’t exactly a ball of fire. Yet in 1980, when the popularity of motorcycling was at post-war peak, the CB250N was the UK’s top-selling bike. That year more than 315,000 bikes were sold, of which more than 17,000 were CB250Ns.

Novice riders of the day were limited to machines of less than 250cc and many didn’t bother taking a test and continued riding with their L-plates. They had a wide selection of bikes to choose from: more than two dozen models from 10 manufacturers who were fighting for a huge market. For most riders there was a simple choice to be made: either the most performance, meaning a fast two-stroke twin like Yamaha’s RD250LC, or something more sedate and reliable, like the Honda CB250N.

Another strong reason for choosing the CB250N was that, in addition to being supported by a massive dealer network, it looked so much more impressive than its competition. Almost identical to Honda’s middleweight CB400N, it projected an image that the rider was in charge of a more potent model – it boosted the rider’s ego. So there’s no wonder it sold in droves.

Another strong reason for choosing the CB250N was that, in addition to being supported by a massive dealer network, it looked so much more impressive than its competition. Almost identical to Honda’s middleweight CB400N, it projected an image that the rider was in charge of a more potent model – it boosted the rider’s ego. So there’s no wonder it sold in droves.

But at Which Bike?, the leading motorcycle buyers’ magazine of the period, we didn’t quite get it. We had tested every one of the 250cc contenders in the class and the universal opinion was that the CB250N was about as exciting as a plate of cold porridge. In an objective three-way 1979 review of the Honda against Yamaha’s XS250 and Kawasaki’s Z250, we concluded that the Kawasaki was functionally the best four-stroke twin in every way.

Clearly few prospective motorcyclists took much notice of that when entering a Honda dealership. The factory was riding high, motorcycles were hot and the CB250N provided a racy-looking and risk-free entry to the world of two wheels.

For Honda, its success at the beginning of the 1980s was the culmination of a strategy to develop completely new ranges of motorcycles with an appeal beyond core enthusiasts. The four-cylinder CB750 in 1969 had established the superbike era, but the factory then concentrated on its automobile range, and the motorcycle division languished. In 1975, with the launch of the Gold Wing tourer, Honda rewrote motorcycling history again by turning North Americans onto long-distance touring. The Wing Nut was born. Simultaneously, motorcycle enthusiasts in Europe were thrilled by the launch of the CB400F, a four-cylinder machine that was less daunting than the CB750 and CB550 fours.

The force behind the flat-four shaft-drive Gold Wing was Honda’s legendary engineer Soichiro Irimajiri, who had led the team that created the six-cylinder Grand Prix machines raced by Mike Hailwood in the mid-60s. Irimajiri’s next project was to design a new range of lightweights that would appeal primarily to the US market, offer superior handling, be less costly to manufacture and meet tougher emissions and noise laws.

At a time when fuel prices were rocketing and the motorcycle boom fired up by the superbikes was waning, rumours spread in the industry that Irimajiri’s project would again create a dramatic shift in motorcycle design to reinvigorate the market.

At a time when fuel prices were rocketing and the motorcycle boom fired up by the superbikes was waning, rumours spread in the industry that Irimajiri’s project would again create a dramatic shift in motorcycle design to reinvigorate the market.

Launched in July 1977 the ‘quiet revolution’, as I then described it, turned out to be a revival of the traditional parallel twin, a format that was dear to the hearts of keen riders on both sides of the Atlantic. Irimajiri had completely rethought the concept however, with claims of high performance, refinement and agile handling as key features of the new bikes.

The focus of the range was the CB400T, a 395cc twin called the Hawk. It was a bid to rekindle memories in the US and was backed up by the automatic CB400A. For the UK and some European markets, the CB400T was augmented by the smaller-capacity CB250T, aimed at European novice riders.

Outwardly identical, the European models were called Dream, with their most striking feature being artillery-style wheels of the type that had first appeared a year earlier on Honda’s works RCB1000 endurance racing machines. The twin-cylinder engines were stubby and compact, mounted high in the frame below a teardrop fuel tank with a deeply padded dual seat and a megaphone-style exhaust system.

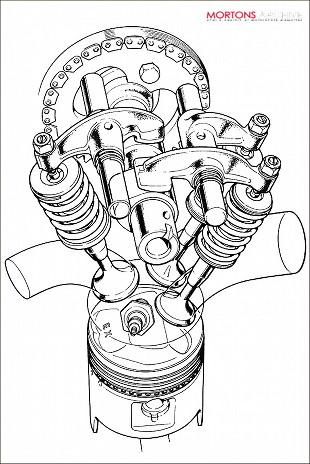

The architecture of the engines was a complete departure from that which Honda had used for its earlier twins, which had 180-degree crankshafts supported in ball and roller bearings along with combustion chambers with two valves. The new high-revving engines were 360-degree twins with the pistons rising and falling together and an ultra-short stroke, with the case of the CB250T internal dimensions of 62 x 41.4mm giving a swept volume of 249cc. The large bore diameter enabled twin inlet valves to be used. This, said Irimajiri, gave better cylinder filling and torque at mid-range revs without sacrificing top-end power and valve gear reliability. A single overhead camshaft driven by a Hy-Vo chain from the centre of crankshaft opened the valves with rockers adjusted by locking screws, the whole assembly accessed under a single cover.

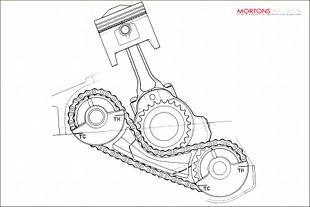

The crankshaft was a steel forging running in plain bearings supported in caps bolted into the upper crankcase half. To minimise vibration from the pistons, two balance shafts driven by a chain rotated in the opposite direction to the crank, their weight opposing the pistons at top and bottom dead centre.

The crankshaft was a steel forging running in plain bearings supported in caps bolted into the upper crankcase half. To minimise vibration from the pistons, two balance shafts driven by a chain rotated in the opposite direction to the crank, their weight opposing the pistons at top and bottom dead centre.

Honda said the design of the engine was influenced by the need for a more compact unit that could be mounted higher and closer to the combined centre of gravity of the rider and machine, enabling the machine to be more agile.

Of the 249cc and 395cc machines at the launch, I preferred the smaller. While the 395cc twin was quick – quicker indeed than the 400 four that it would replace – it had a buzzy character that I didn’t enjoy much, despite excuses from Honda staff who said the bikes were pre-production prototypes. The CB250T was much more satisfying with a silky power delivery and nimble handling. While peak power was a claimed 26.6bhp at a heady 10,000rpm, the urge was smooth throughout the rev range with clean response from the 28mm Keihin CV carburettors.

Mid-range torque was said to be also improved by the exhaust system, in which the twin-walled down pipes fed into a ‘power-chamber’ behind the gearbox which then exhausted through two dumpy silencers, the assembly being masked by chrome-plated covers to give the impression of a conventional exhaust system. Helping to broaden the delivery was an ignition system of extraordinary complexity for the time. Each cylinder’s spark plug was fired by a capacitor discharge system with an advance curve controlled by three pickups adjacent to the alternator.

The UK launch was held on the twisty roads of Gloucestershire and the Welsh Marches where the CB250T could still be wound up through the five-speed gearbox to reach an indicated 85mph. But despite being almost identical to the CB400T the smaller bike’s high-speed handling wasn’t quite as secure. For the first time, Honda was using its so-called FVQ rear shocks which used a damping medium that was said to make use of emulsified oil rather than suffering from it. The neat-looking Comstar wheels, with light-alloy rims riveted to chromium-plated pressed-steel spokes in traditional 19in and 18in sizes, were fitted with grippy Bridgestone tyres that enabled confident cornering on the 400 at speeds that would make the 250 all frisky at the rear.

The UK launch was held on the twisty roads of Gloucestershire and the Welsh Marches where the CB250T could still be wound up through the five-speed gearbox to reach an indicated 85mph. But despite being almost identical to the CB400T the smaller bike’s high-speed handling wasn’t quite as secure. For the first time, Honda was using its so-called FVQ rear shocks which used a damping medium that was said to make use of emulsified oil rather than suffering from it. The neat-looking Comstar wheels, with light-alloy rims riveted to chromium-plated pressed-steel spokes in traditional 19in and 18in sizes, were fitted with grippy Bridgestone tyres that enabled confident cornering on the 400 at speeds that would make the 250 all frisky at the rear.

A month later, the first road test machine supplied to the weekly paper Motor Cycle, was much improved with handling to match its stature. You could use all of the generous cornering clearance and even when the folding footpegs were skimming the road and the back end was skittering it never felt anything but solidly planted. I also liked the riding position, the slightly raised handlebar grips and narrow fuel tank allowing you to tuck in comfortably, and better cope with the compromised stability at high speeds.

With the opportunity to ride the bike in a wider range of conditions I was able to find out more about the performance of the newly designed disc brake. This used a floating caliper with a single slave piston and a window through with you could check the pad wear. Honda reckoned the caliper design – being mounted behind the fork leg and with different disc material –offered better wet-weather performance, but it was no better than the earlier design in the wet and in fact less potent in the dry.

On MIRA’s test strip I found that the CB250T’s performance was better than its reputation might suggest. It was correctly geared with a mean top speed of 87.8mph, with the engine revving at just below 10,000rpm. For those who reckon the CB250T’s performance was poor, this top speed was within 1mph of the CJ250T it replaced, and Yamaha’s XS250 four-stroke twin. What conspired against the CB250T was its weight, and that stunted its acceleration compared with the lighter – by more than 30 pounds – and more powerful two-stroke 250s. But with a quarter-mile time of 17.2 seconds with a terminal speed of 75.2mph it was an improvement on previous 250cc Hondas.

On MIRA’s test strip I found that the CB250T’s performance was better than its reputation might suggest. It was correctly geared with a mean top speed of 87.8mph, with the engine revving at just below 10,000rpm. For those who reckon the CB250T’s performance was poor, this top speed was within 1mph of the CJ250T it replaced, and Yamaha’s XS250 four-stroke twin. What conspired against the CB250T was its weight, and that stunted its acceleration compared with the lighter – by more than 30 pounds – and more powerful two-stroke 250s. But with a quarter-mile time of 17.2 seconds with a terminal speed of 75.2mph it was an improvement on previous 250cc Hondas.

Fuel consumption was surprisingly variable. Given a gentle throttle hand you could return 60mpg for a range of 150-miles to reserve, but when thrashed the bike’s consumption dipped dramatically, so the test consumption was a poor 46.9mpg.

'But despite this I have to say I liked the CB250T. The nimble handling, grippy tyres, reliable starting (if long warm up) and comfort made it one of the better day-to-day bikes to ride.'

But despite this I have to say I liked the CB250T. The nimble handling, grippy tyres, reliable starting (if long warm up) and comfort made it one of the better day-to-day bikes to ride. Of course, the 400 would be better, but for a first-timer there are few to better it.

But Honda did, and in double quick time. Less than a year later – and following the launch of the radical CX500 V-twin and dramatic six-cylinder CBX – in the summer of 1978 the factory revealed its Euro-styled range which included the CB900F four, along with the CB400N and CB250N Super Dreams redesigned to cater to more sporty European tastes.

Changes were much more than the eye-catching restyle job. Power was claimed to be increased by around 12 percent so that the peak 26.6bhp at 10,000rpm was at the rear wheel rather than at the crankshaft. This was achieved with a new cylinder head using revised inlet and exhaust port shapes, and combustion chambers though the compression ratio was unchanged at 9.4:1. The silencers were lengthened to improve throttle response the crank’s flywheels were slimmed by 2.3 pounds.

Changes were much more than the eye-catching restyle job. Power was claimed to be increased by around 12 percent so that the peak 26.6bhp at 10,000rpm was at the rear wheel rather than at the crankshaft. This was achieved with a new cylinder head using revised inlet and exhaust port shapes, and combustion chambers though the compression ratio was unchanged at 9.4:1. The silencers were lengthened to improve throttle response the crank’s flywheels were slimmed by 2.3 pounds.

Although maintenance chores were fairly straightforward, with oil changes every 2,000 miles, it had been found that the engine’s balancer drive chains would benefit from closer attention. So the clutch cover was modified with a small cover providing access to the chain’s adjusting mechanism. Six speeds were used in the gearbox, rather than five, although the final drive ratio was unchanged, raising the top gear ratio from 8.24 to 7.95 to 1, with Honda claiming that top speed had been raised to 146kph (90.7mph).

As part of the restyling, the riding position was also given an injection of aggression with the seat nose moved back by about two inches, along with the foot rests by four inches, and lowered, with the handlebar by almost two inches. Removal of the bolt-on seat exposed the toolkit and air-filter cover.

But the chassis, comprising a pressed-steel spine and incorporating the engine, was still long and large with a 55in wheelbase. An improvement in road-holding was expected with Comstar wheels that used lighter aluminium-alloy spokes, complementing changes to the rear shocks with slightly stiffer springs and stronger spindles.

The CB250N was taken to MIRA a few months later where Honda’s claims for higher performance could be put to the test. Although just as fine-handling a road machine as its predecessor and enhanced by the closer ratios on country roads, it felt breathless at higher speeds in top gear. The 1000-yard timing straight at MIRA takes no prisoners. John Simcock, a colleague at Motor Cycle, wound up the twin but the best one-way speed he could achieve was just 88.2mph with the help of a tailwind and the engine revving to just 9800rpm in top gear. The average of the two best opposed runs was only 82.9mph. An indication that this particular machine’s power was below par came with the acceleration figures. A quarter-mile time of 17.5 seconds with a terminal speed of 74mph was down on the previous CB250T.

The CB250N was taken to MIRA a few months later where Honda’s claims for higher performance could be put to the test. Although just as fine-handling a road machine as its predecessor and enhanced by the closer ratios on country roads, it felt breathless at higher speeds in top gear. The 1000-yard timing straight at MIRA takes no prisoners. John Simcock, a colleague at Motor Cycle, wound up the twin but the best one-way speed he could achieve was just 88.2mph with the help of a tailwind and the engine revving to just 9800rpm in top gear. The average of the two best opposed runs was only 82.9mph. An indication that this particular machine’s power was below par came with the acceleration figures. A quarter-mile time of 17.5 seconds with a terminal speed of 74mph was down on the previous CB250T.

The one positive was that fuel consumption had improved. Indeed, in the constant fuel consumption tests the Super Dream recorded 100mpg at 30mph and 52mpg at 70mph with an test average of 54mpg.

So is a 250cc Super Dream appealing as a classic? The argument is just the same as when it was launched. If you’re interested in a slice of 1980s motorcycling and can find an example that is clean and unblemished, give it a try – it won’t break the bank, and you might enjoy it. ![]()