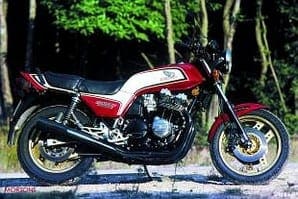

Produced in 1983 for the US and European markets (it was inexplicably not an official UK import), the 1100F had the same air-cooled four-cylinder engine but with less of the hand-crafted attention that made the 1100R so much of a cult bike. Nonetheless, the 1100F offered much of the 1100R’s 140mph performance in a more practical package, and provided a stopgap in Honda’s model line-up in advance of the following year’s launch of a more potent range of V-fours led by the VF1000R.

Honda had launched the sporty CB1100R at the end of 1980 as a limited-production homologation model intended to blow off the opposition in the increasingly popular production racing championships for box-stock bikes in the UK, Australia and South Africa.

Based on the CB900F, the R had an overbored engine with high-performance camshafts, but what made it special was a number of lightened components topped off with a red-painted frame in thinner tubing, ventilated brake discs, bigger aluminium fuel tank, fairing and racing-style single seat.

Based on the CB900F, the R had an overbored engine with high-performance camshafts, but what made it special was a number of lightened components topped off with a red-painted frame in thinner tubing, ventilated brake discs, bigger aluminium fuel tank, fairing and racing-style single seat.

It did the job. Ron Haslam ran away with the Shell-sponsored series in the UK in 1981, making the CB1100R an instant classic enhanced by its rarity. In three years just 4050 were made for sale worldwide.

It was also very expensive at £3700, a massive 80 percent premium over the CB900F in 1981.

Which is probably why, with Suzuki and Kawasaki locked in combat with their own 1100cc Superbikes, Honda jumped into the fray in 1983 with the CB1100F priced just low enough below the opposition to make riders think again about the virtues of a model series that had been around for five years.

Not that there was much wrong with the Honda package that had been launched at the end of 1978. Quite simply, everything about the original CB900F design was just right. OK, you could complain about minor details of its performance and reliability, pointing to the clutch, suspension and engine vibration, but it was otherwise spot on. Honda’s engineers got the ergonomics right; items like the hand and foot controls, the mirrors, the build quality, the sleek bodywork, all enhanced the experience from first contact.

Subsequent versions of the CB900F were improved with more adjustable suspension, wider and smaller-diameter wheel rims, that could take more up-to-date tyres, and vibration-absorbing engine mounts to smooth the ride at speed.

So there wasn’t much reason to make many alterations to the CB900F from the 1982 model range when the CB1100F was conceived to rattle the cages at Kawasaki and Suzuki. Just make it more potent.

Honda had already shown with the CB1100R that there was plenty of room in the engine’s architecture to use the simple expedient of increasing its capacity. The CB900F was always peculiar in that it used under-square bore and stroke dimensions of 64.5x69mm, ostensibly to make it narrower.

Using bigger cylinders bored to take 70mm pistons increased the capacity to 1062cc for an immediate power lift. Along with longer-duration and higher-lift camshafts, a higher compression ratio and larger-bore carburettors, peak power was boosted from 95bhp at 9000rpm to 110hp at 8500rpm, more than the six-cylinder 1047cc CBX’s 105bhp.

Using bigger cylinders bored to take 70mm pistons increased the capacity to 1062cc for an immediate power lift. Along with longer-duration and higher-lift camshafts, a higher compression ratio and larger-bore carburettors, peak power was boosted from 95bhp at 9000rpm to 110hp at 8500rpm, more than the six-cylinder 1047cc CBX’s 105bhp.

While this was more than welcome (the peak was just five ponies less than that claimed for the R), what made the CB1100F more appealing than the Kawasaki or Suzuki was a huge hike in mid-range grunt combined with silky refinement and smoothness.

Peak torque was raised by nearly 30 percent to 71.5 ft-lb at 7500rpm but the urge was stronger all through the range, allied to clean throttle response from the larger 3mm Keihin CV carbs. In a top-gear roll-on from about 40mph alongside Kawasaki’s GPz1100R, the Honda would pull away until reaching 120mph when it would be overhauled by the higher top-end power of the Kwak. In most practical circumstances the Honda offered a less frantic partnership.

It was also much more comfortable. High-frequency vibration was always the bane of in-line four-cylinder engines and Honda overcame this by rubber mounting the engine on the later CB900F models, carrying it over on the CB1100F.

To ensure that the rubber bushes aren’t compressed by the drive chain loads Honda used a pair of small links between the frame and front of the engine, keeping the engine in line while absorbing the largely vertical vibration forces.

That, along with a relaxed riding position and accommodating seat, makes the 1100F a more cosy partner for long rides with practical cruising speeds up to 90mph behind the small handlebar fairing.

Taming machines with more than 100 unruly horses was never quite mastered by the Japanese factories in the early 80s. Honda managed the problem with the 1100R, but the need for wider appeal on the 1100F compromised high-speed handling.

Two versions of the 1100F were offered. For Europe, the wheels were the familiar Comstars with forged-aluminium-alloy boomerang spokes and a light-alloy box-section rear swingarm. For the US, it came with cast-alloy wheels and a swingarm in box-section steel (though some have the light-alloy arm). Changes to the frame included a revision of the steering geometry, changing the steering head angle from 62.5 to 61.5 degrees and increasing the trail to 120mm while lengthening the head length by 28mm, both of which had been used in US Superbike racing.

There was not much difference in the handling between the two versions. Although offering reasonably light steering and neutral handling – much better than you’d expect of a machine weighing 592lb tanked up – both versions still suffered from a measure of instability during high-speed cornering, showing a propensity for slight weaves that couldn’t be dialled out by adjustments to the suspension.

There was not much difference in the handling between the two versions. Although offering reasonably light steering and neutral handling – much better than you’d expect of a machine weighing 592lb tanked up – both versions still suffered from a measure of instability during high-speed cornering, showing a propensity for slight weaves that couldn’t be dialled out by adjustments to the suspension.

Like the CB900FD, the 1100F came with rear shocks offering both spring preload adjustment and separate adjustments for both bump and rebound damping. Up front the telescopic fork with larger-diameter 39mm legs had air-pressure assist for the springs and anti-dive valving for the adjustable compression damping.

Under braking, the dual-piston calipers applied pressure to the valves, increasing the damping and reducing dive. Along with discs that offered the best feel and response in the class, the system also worked better than most.

The CB1100F was therefore the last of a line of classic-styled air-cooled Honda fours that had started in 1968 with the CB750. It may not have offered the blinding speed of the potent GPz1100R, or the sizzling mid-range of Suzuki’s GX1100E, but the CB1100F was a fine amalgam of an iron fist in a velvet glove. ![]()