Words: Steve Cooper | Photos: Gary Chapman

Scoop samples a rather obscure 1960s 125 – the Puch M125 – and comes away rather impressed.

More than a decade ago I was offered a strange looking Austrian 125cc motorcycle, but at a meaty price. It was said to be the very bike featured on the front cover of our forerunner, Motorcycle Mechanics. I looked, examined and kicked the tyres as you do but then politely declined. After all this time another one comes up on my radar and we’re offered the chance of a road test.

Other than the VZ50 that we ran in Buying Guide a little while ago, I really cannot recall the last time CMM featured a Puch. Although the Austrian firm was a significant player in the motorcycle world for decades, the marque was never especially well represented in the UK other than in the moped market. Their motorcycles were always well made and utilised quality components from well-known suppliers within Europe but this, allied to the old Austrian Schilling-UK GBP exchange rate, meant the end products were never cheap here in Blighty.

Nowadays the marketing guys would spin the cost of an M125 Puch by saying it was a niche model made up to specification, not down to a price. However, our test bike hales from the very late 1960s, a period when small capacity motorcycles were still perceived as commuter transport, not recreational vehicles.

Stacked up against the likes of BSA’s 175 Bantam, few blue-collar workers of the period would have given the M125 a second look, given that it was 50ccs smaller yet cost more.

The first thing that strikes you about the Puch is the fact that it isn’t actually that small, well, not in the way an early Japanese 125 was. It’s actually a relatively substantial motorcycle and one that’s been designed with neither a British or Japanese mind set.

Secondly, the few that know anything about the model will spot a couple of non-standard fitments, but these have been added in the names of usability and safety. Generic, eBay sourced, switch gear replaces the OEM kit that hadn’t weathered the decades too well and some Fizzy-type pattern indicators give anyone nearby ample warning of rider intentions. Other than that the bike is genuine Austrian Puch as it left the factory.

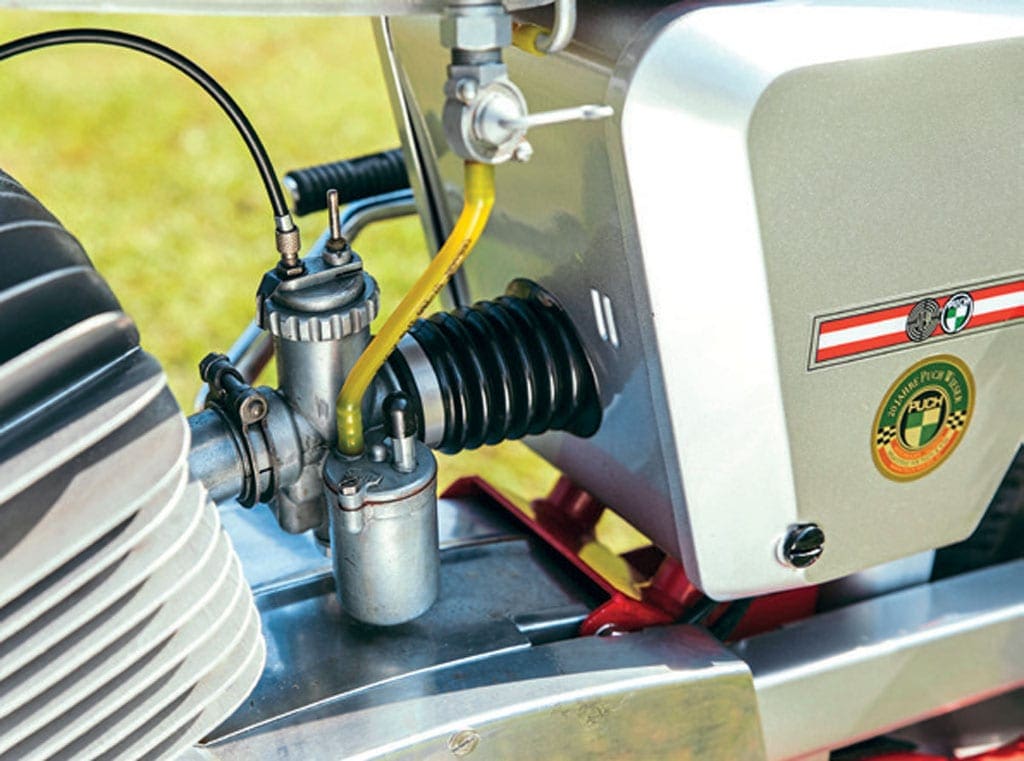

The most obvious stand-out feature of the bike is that red chassis which, when set against the metallic silver of the panel work, gives the bike a unique look given the period in which it was sold. The engine is a simple piston-ported two-stroke single, yet everything about it shouts high quality. There’s deep, multiple finning on the barrel and a seriously effective, heat-dispersing, radially-finned cylinder head, which strongly suggests Puch didn’t want their high-class tiddler seizing whatever the terrain or weather.

The bike has elements of both the old and new about as it moved towards the 1970s. By then even the Japanese had grasped that motorcycle theft could be an issue, yet Puch saw no reason to fit an ignition switch, instead gifting the M125 just a kill button. Perhaps, a little perversely, the bike runs plastic side-panels, yet the air-box they cover is made from cast alloy; you begin to realise that this most definitely is not your average, humble, pre-mix commuter.

Being Austrian, the bike is by default Teutonic in design and build, yet due to its geography the factory’s buyers apparently looked all over Europe for the component parts they didn’t have in-house. Both front and rear lights are CEV Italian, as is the seamed, shark’s gilled, Silentium Jet ‘silencer’… more of which later.

This unit must have been serious business for the Italian producer as, beneath their logos, there’s a ‘PUCH’ stamping, suggesting that the Austrian firm was ordering in decent numbers and had some serious clout with their suppliers.

The speedo is high-end German VDO and the same goes for the carburettor which is marked BING; everywhere you look the bike almost drips quality. And then you get to the seat, which was supplied by none other than Denfield of West Germany. That name probably means little to many, but anyone who has had dealings with earlier BMWs will know that Denfield were the preferred supplier of official accessory seats to the Bavarian firm. It’s a work of art being built around a perimeter frame and sprung base rather than a steel pressing and some foam.

Once sampled you’re likely to be an immediate convert to the apparently archaic set up. The best analogy I can give is finally getting to sleep in your own bed rather than lying on an Argos-sourced futon for the weekend! Another easily overlooked feature is the adjustable footrests, which facilitate a reasonably wide range of adjustment allowing the pilot to fine tune the riding the position.

With no ignition key, firing up the M125 is simply a case of turning on the fuel and kicking the engine over. That this bike is a product of the 1960s is in no doubt as the silencer barks out its raucous tone. The notion of noise pollution was only just getting popular coverage when the Puch first turned a wheel and, as we know from previous experience, Italian manufacturers firmly believed bikes and cars should be heard as well as seen. Also vying for attention is the rather profound fin ringing from fairly prodigious alloy castings – this isn’t going to be quiet ride then.

The clutch is light in operation and predictable, regardless of how hot the engine gets. The four-speed gearbox is precise in use, overtly mechanical yet not agricultural; it’s not slick like a Japanese transmission, yet neither is it clunky like certain East European offerings.

Its one foible, by dint of having just four ratios, is the significant gaps between each gear. Whereas contemporary Japanese machines would have run three fairly closely spaced first, second and third then have top (fourth) almost as an overdrive, the Austrian bike has all four gears evenly spaced. This, therefore, requires the rider to work the engine relatively hard if the next upward change isn’t going to leave the engine bogged down outside the power band.

All credit to the simple engine; it takes all this abuse and more without issue or complaint. The engine is relatively buzzy at lower revs and some vibration does get through to the bars, but it disappears as the revs rise. The more you ride the bike the more you realise it’s not a commuter slogger in the way machines such as BSA Bantams, CZ175s or MZ TS150s – it likes be worked and worked hard.

….For the full feature, pick up the January 2020 issue of Classic Motorcycle Mechanics. For more information on how to get your hands on a copy, click HERE.