Every now and again a motorcycle comes along which sets completely new standards of performance, handling or sophistication and which proves to be, in time, a trend setter.

The Honda Fireblade, Kawasaki GPZ900R, Kawasaki Z1… and the BMW R90/S.

More than 25 years after its launch, most people have forgotten its initial impact. But this was a bike which set a styling trend that still persists today, and it was the fastest old-style boxer ever built.

In the early 1970s BMWs were seen as luxury tourers. Expensive, well-built and finished: gentleman’s expresses. But not sportsters. Oh no. Possibly the last sporting BMW had been the R69S. The then BMW 75/5 was better behaved than many so-called sports bikes, and fast point-to-point in the tradition of BMWs that still persists today, but exciting? No, not really.

The R90S changed all that in late 1973. For a start, it was 150cc bigger; the same capacity as its contemporary, the mighty Kawasaki Z1. Secondly, it boasted a high compression ratio of 9.5 to 1. Thirdly, it was fitted with a pair of slurping great accelerator-pumped 36mm Dell’ Orto carbs instead of quirky Bings.

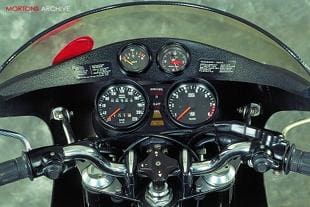

Fourthly, the front end boasted twin discs – the Honda CB750 and the Z1 only came with mounts for optional second discs. Fifthly, it was incredibly well equipped, with instrumentation that included a voltmeter and a clock (the last time anyone had seen a clock on a bike was on the old Ariel Leader), cockpit fairing, halogen headlight, and even a tyre pump. Finally, it was styled in a manner that made jaws drop.

The fairing set off the front of the bike. The tank blended smoothly into the seat, which rose slightly at the end to match up to a little Kawasaki-style ducktail.

Best of all was the paintwork: two-tone grey, or two-tone orange, with an incredible hand-applied smoked effect where the two colours blended together. Quite apart from anything else, the smoked effect paint meant that no two bikes were ever quite identical.

All this was enough to inspire the respected technical writer L.J.K. Setright to declare it “possibly the best production motorcycle in the world.” At £1800, or twice the price of the CB750, or 50% more than the Z1, it should have been.

The R90/S was quick enough to race. Its top speed was about 130mph. Few magazines had access to electronic timing apparatus in those days. Bike magazine did in 1975 and timed a 90/S at 126mph with a 13.2 second standing quarter.

Acceleration on the 90/S was particularly vivid because the accelerator pump-equipped carbs squirted great gobbets of fuel into the cylinders when you yanked open the twistgrip.

In racing, the bike did quite well in endurance and even on short circuits, although cornering clearance was always limited by the rocker covers grounding. Some racers used to carry spare rocker covers strapped to the bike so that when they wore a hole through, they could do a swift change before they lost the oil.

The BMW also handled better than any Japanese offering. It wasn’t quite as good as the best Italian stuff and maybe not as precise as the best British, but it was very, very good for the day. Soft suspension, as ever, was one of its problems but that was relatively easily rectified.

The main frame downtubes were inadequately braced and some racers welded a cross-piece between the tubes to stiffen them. BMW acknowledged this weak spot by similarly bracing its frames from the /7 series. The rear subframe, which carried the rear shocks, was bolted on and therefore prone to flex under severe conditions.

The biggest problem was the tendency of the 90/S to break into high-speed weaves and wobbles. It didn’t affect all the bikes (rider weight seemed to have some effect) and could be alleviated by screwing down the standard steering damper between the clocks.

In those pre-wind tunnel days, people suspected (but couldn’t prove) that the bar-mounted fairing was to blame. Today we know they were right.

I remember blasting a friend’s 90/S in the South of France in the early 1980s when I ran a Guzzi Spada. It was at least 10mph faster than the Spada but at anything over 90 the Spada completely out-handled it.

What goes wrong

What goes wrong

It’s a BMW so it’s reliable and long-lived. However, with its growth to 900cc, the engine started showing the first signs of strain which became plain when BMW hogged it out to the full litre. Oil misting and even leaks from the base of the barrels is common. The clutch, unmodified to cope with the extra power, doesn’t last as long as on some.

The spokes should be regularly checked in the rear wheel – 67 horsepower and shaft drive through an unforgiving transmission doesn’t treat spokes kindly.

Seat covers split with age but that’s a minor detail. By and large, the only problems will be those associated with age; faded paint, dull chrome (not that there is much) and crash damage.

What to buy

If it’s been restored, check you aren’t being offered a tarted up R90/6, the ‘cooking’ version. This only got a single front disc and no fairing but, like all BMWs, commonality of parts means it’s easy to convert a /6 to /S spec by adding the fairing and carbs.

Unfortunately, the /6 also got a lower compression ratio and that’s less easily checked. Another key difference is shorter final drive gearing – 3.09:1 instead of 3.00 to 1. Actually, if you wanted, you could specify your R90/S with 2.91:1 final drive for even more long-legged cruising at the expense of acceleration.

Restoring a 90/S is tricky because few people can actually replicate that amazing paint scheme. Quite a few 90S/s wore leather tank covers to protect the paint and thus have survived quite well.

Parts availability for old boxers is still good but the number of special tools needed for dismantling an engine is amazing. A dealer rebuild will be expensive. Whatever you buy, it won’t depreciate. ![]()