Assuming you run a Japanese four cylinder motor you will almost certainly have four carbs, one for each pot. When you open the throttle you need all four carbs to respond at the same time so each cylinder gets the same amount of fuel and works with its neighbours.

In real life this means that each slide (or butterfly if you have CV carbs) needs to start to move at exactly the same time and all four slides (or butterflies) should be exactly parallel. This means all the cylinders get exactly the same rush of fuel and work together as a team.

If the carbs are not synchronised to work together the engine gets conflicting signals as one cylinder is told to accelerate when its neighbours are still idling.

Back in the days of Bonnevilles and Commandos the twin carb set-ups were operated by a pair of throttle cables, one for each carb. To balance the carbs all you needed to do was hold the twistgrip wide open, stick a finger into each carb mouth and feel where the throttle slides were. Then you’d adjust the throttle cables to make sure they were both at the same height.

One-into-four

Very early 750 Hondas had a one-into-four throttle cable assembly which called for a similar technique. Pretty quickly the Japanese factories figured out a way of operating all four carbs from a common link rod, operated by a single cable wrapped around a central rotor.

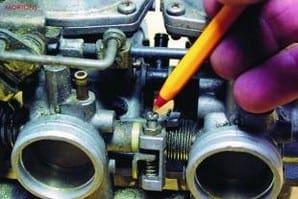

To synchronise the carbs, small adjusters were fitted to the link rod so you could alter the relative position of each slide to its neighbour. When the CV carb came along the throttle link rod and adjuster stayed. And that’s the system most of us still have, more or less.

In theory you can balance four cylinder carbs by removing them from the bike and doing it by eye. On a bank of slide carbs trap a small piece of wire (I use short lengths of welding rod) under each slide, swivel the carbs round so all four mouths are facing downwards, then very slowly open the throttle slightly. Note which piece of wire falls out first and which last. Make adjustments to the balancer screws until all four pieces of wire fall at exactly the same time when you open the throttle. Bob’s your uncle…

In theory you can balance four cylinder carbs by removing them from the bike and doing it by eye. On a bank of slide carbs trap a small piece of wire (I use short lengths of welding rod) under each slide, swivel the carbs round so all four mouths are facing downwards, then very slowly open the throttle slightly. Note which piece of wire falls out first and which last. Make adjustments to the balancer screws until all four pieces of wire fall at exactly the same time when you open the throttle. Bob’s your uncle…

However, one more factor needs to be considered to get the carbs exactly right. The amount of fuel going into the engine is not only affected by throttle position but also by how much induction the engine has – which in turn depends, of course, on the condition of the piston rings, valve seats and tappet clearances.

Assuming your engine internals are all wearing at slightly different rates (usually the case in real life), the cylinders might each need slightly different throttle settings to get them to work in perfect unison.

So for the best results we can measure the induction, or vacuum, at each cylinder, then adjust the carb balancing screws so all are the same. The good news is you can do this with the carbs on the engine. The bad news is you need special vacuum gauges and the engine has to be running while you work on it.

Take-off points

All bike engines will have take-off points to attach vacuum gauges, usually on the rubber stub supporting each carb. Kawasaki and Yamaha, for instance, have a short brass tube sticking out of each inlet stub, blanked off with a rubber cap. Suzuki favour a small brass screw fitted into the cylinder head next to the inlet stub. Some machines with inaccessible carb intakes may have extended take-off points – look for four lengths of capped-off tubing, and it’s here where you connect the vacuum gauges.

Hook up the gauges to these four take-off points, using adaptors if you have the Suzuki type, rig up a temporary fuel feed if you’ve had to take-off the tank, fire up the motor and look at the gauges to see exactly what’s happening.

If you have one cylinder reading higher than the others try turning that carb adjuster screw one way or the other and see what happens. Play around with the adjusters until all four gauge needles are level, then blip the throttle a couple of times, let the gauges settle and check the settings. It doesn’t matter what numbers the gauges actually read, you’re aiming to get all the needles parallel.

You’ll probably find that if you set everything up perfectly at tickover, then hold the engine at 4000 rpm, you’ll get different readings. On anything other than a brand new bike you may have to compromise the settings to get the engine smooth at the rpm which suits you, maybe sacrificing an even tickover for perfect tune at motorway cruising speeds. It’s dependent on your type of ride – town commute or out in the open. ![]()