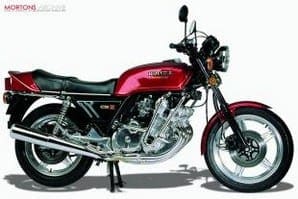

This is pure classic. Undisputed, 100 percent, hallmarked classic. Odd, then, that it was a relative sales failure.To understand the CBX you have to go back to the Honda range of the mid-Seventies. Honda had a range of stodgy twins from 175 to 500cc and a range of fours that were almost as stodgy.

Reliable, well engineered, but a tad dull. Only the immortal CB400/4 had any glamour and that was about to be killed off because the Americans weren’t buying it. At the same time, the opposition was challenging Honda in all markets with bikes that were simply more exciting, faster and more fun.

Honda took its corporate eye off the ball while it developed its car range. In the nick of time, somebody sounded the alarm bell and the motorcycle team started working on new models. In 1978 they launched two stunning bikes, as different as chalk and cheese. One was the CX500 vee twin. The other was the CBX six.

The last time Honda had made a six it had been the awesome racer that propelled Mike Hailwood to TT victory in the 1960s. Honda’s corporate PR made much of the fact that the CBX was a direct descendant of the 250cc racer and, in the sense that it had the same number of cylinders and the same number of valves (24!), it was. Otherwise, the CBX was really quite a conventional aircooled engine.

The last time Honda had made a six it had been the awesome racer that propelled Mike Hailwood to TT victory in the 1960s. Honda’s corporate PR made much of the fact that the CBX was a direct descendant of the 250cc racer and, in the sense that it had the same number of cylinders and the same number of valves (24!), it was. Otherwise, the CBX was really quite a conventional aircooled engine.

Sixes had been built before. Benelli had its 750 (essentially a Honda 500/4 with two extra pots) which it later enlarged to 900cc. Four-valve heads had been around since the days of the Rudge. Yamaha’s XS500 twin had them in 1974. Honda’s Motosport 250 off-roader had them even earlier. But nobody had ever married the two.

With a claimed power output of 105 bhp, the CBX was at least 15hp more powerful than anything else on the road. Its specific power output wasn’t that great, actually – 105 bhp for 1047cc is exactly 100 bhp per litre, indicating that the CBX had plenty of potential for tuning.

To house the engine, Honda built a spine frame and hung the engine from it. No downtubes spoiled the view of the engine. It was, and is, a styling masterstroke. From the front all you could see was a magnificent motor and six exhausts curling round under the block. With the 400/4, Honda’s stylists learned how one could use the visual impact of an engine block and exhaust: now they re-applied the lesson.

Attention to detail showed in the carburettors. With a wide block, the carbs would obviously foul the rider’s knees so Honda angled the inlet tracts into the centre of the bike and the 28mm carbs could be tucked out of the way. Obviously, for ultimate power, straight inlet tracts would have been better but then the CBX wasn’t in a particularly high state of tune anyway.

To keep the engine narrow, the alternator was mounted piggy-back behind the block. Common practice now but revolutionary thinking then. The result was a motor that was actually only two inches wider than the sohc CB750.

During development of the bike, Japanese engineers went and sat outside a US Air Force base in Japan and recorded the sound of jet fighters (F4 Phantoms, for the record). They actually duplicated the sound in the CBX’s exhaust note. The story goes that Soichiro Honda himself forbade it, saying that motorcycles should not sound like weapons. It would be interesting to know if any of those sound recordings of the development CBX with its jet fighter exhaust have survived.

The cam cover was a one-piece casting. The cams were actually two-piece, joined in the middle via an Oldham coupling. The camchain drove the exhaust cam and the inlet cam was connected to the exhaust cam by a separate smaller chain. Honda was to use this system on the 750cc and 900cc fours that followed. The valve gear was also used on the fours; the adjusting shims are identical.

New forks and rear suspension were adorned with new floating-piston brakes. Even at the launch the handling was questioned. Honda themselves admitted that it wasn’t perfect, but adequate; a fair assessment. One problem was that the swinging arm was supported on plastic bushes which wore out fast. But the main thing was the way it looked and went. 140 mph was Laverda Jota territory then.

The engine was just so driveable – it pumped out torque from 2000 rpm and as the revs rose it just piled on more and more power. And the revs rose fast. It was supremely flexible and it was smooth.

So why didn’t it sell?

So why didn’t it sell?

Two reasons. First, it was never a cheap bike. In late 1978 it was priced at £2800 and the equally new Yamaha XS1100 was £700 cheaper. Secondly, Suzuki launched the GS1000 which had all the performance of the CBX coupled with much lighter weight, brilliant (for the era) handling and a price tag £1000 less.

If you wanted ultimate performance, you bought the GS1000. You bought the CBX simply for its glorious engineering. Most people put performance above engineering. If those six cylinders and 24 valves didn’t make it any quicker than four cylinders and eight valves, what was the point?

Bike concluded its test by saying; “Luggage racks and panniers just aren’t for this bike.” In the ultimate irony, Honda developed the CBX not by extracting more power from that superb engine but by adding panniers and a fairing. Yup, we got the CBX-C with the half fairing from the CB900F2 and a matching pair of panniers on the back. Unbelievable. Oh, and it had five bhp less power. The Pro-Arm monoshock rear end was an improvement, as were the uprated brakes, but the problem was that the fairing and panniers made what was already a heavy bike even heavier.

With a gallon of fuel in the tank the original CBX weighed 572 lbs. The C model was 25 lbs heavier. Performance dropped to CB900 levels and it wasn’t much good as a touring bike anyway. The fairing was okay but the panniers were too small, the seat too hard and the fuel range inadequate. Honda dropped the C model after a year or two of lacklustre sales and that was the end of the CBX.

What goes wrong

The engine demands careful servicing. A CBX that’s properly in tune just purrs. A few years ago I rode a superbly restored one and when you started it from cold and knocked off the choke early, the engine turned over without the tacho needle even moving from the stop! It just went ‘swish, swish, swish’.

However, you need a set of six vacuum gauges for the carbs, and adjusting all those valves takes time. An out-of-tune CBX sounds clattery, even if most of the noise is clutch rattle. It’s harmless but you want one that’s been looked after. The camchain arrangement is the same as the CB900, as we’ve seen, and it’s a bit prone to gremlins. Any rattles from the top end mean the tensioner’s had it. If it’s been ridden any distance with a duff tensioner, the camchain will be scrap and that, my friend, means a full engine strip. Oh joy. Moral; avoid rattlers.

However, you need a set of six vacuum gauges for the carbs, and adjusting all those valves takes time. An out-of-tune CBX sounds clattery, even if most of the noise is clutch rattle. It’s harmless but you want one that’s been looked after. The camchain arrangement is the same as the CB900, as we’ve seen, and it’s a bit prone to gremlins. Any rattles from the top end mean the tensioner’s had it. If it’s been ridden any distance with a duff tensioner, the camchain will be scrap and that, my friend, means a full engine strip. Oh joy. Moral; avoid rattlers.

There are aftermarket needle roller bearing kits to replace the useless swinging arm bushes. You can’t do much about the brakes except beef them up with steel hoses and new fluid. When I rode that restored one, it was the (lack of) brakes that worried me. This is a big, heavy bike and under hard use the brakes tend to fade.

You used to be able to get crash bars to protect those vulnerable cases. A rubber pad sat between the bars and the casing ends. Obviously, any CBX that’s been badly dropped and hasn’t got engine bars will probably have damaged crankcases. This sort of damage is quite easy to spot though.

The original exhaust is expensive. Jama do a pattern system that looks identical although, irritatingly, their name is stamped on the top of the silencers where it shows. Why not underneath? There are various six-into-one kits that exist for the (relatively) skint, and a CBX breathing through a decent six-into-one sounds magnificent. Like a Phantom, dare I say?

One thing to beware of is a bike that’s been laid up for a couple of years or more. Unless the carbs were properly drained, the fuel in them will have evaporated or gone off and all the jets and tubes will need removing and cleaning properly. And that will be a big job.

If you want to restore one to stock, remember that items like seats are very hard to obtain and the little bits of trim on the seats next to unobtainable. There are used fuel tanks and clocks to be found at autojumbles but they won’t be cheap.

One thing that makes the CBX expensive to restore is that so many parts are unique to it. Look at one some time. Just look at it, from a distance. It doesn’t look too big, does it? It’s only when you get close do you realise that everything on it is larger than life; the clocks, headlight, tail-light and indicators all look familiar Honda stuff but they’re all scaled up to give the effect of reducing the size of the whole bike.

It is, in fact, bloody massive. That’s a wonderful styling trick but it does mean that you can’t source parts from another bike. The CBX was unique. ![]()