In 1968 Honda launched the CB750. Jaws dropped, particularly at BSA–Triumph HQ, because the recently released three-pot Trident and Rocket lll had just been comprehensively upstaged. Meanwhile, according to lore, Kawasaki's plans to put their own 750 four on the market are shelved while they set to work on a bigger engine. In 1972 the dohc, 903cc, Kawasaki Z1 burst onto the scene making everything else look staid and boring. Honda has temporarily forgotten about bikes to concentrate on cars. By coincidence, the Gold Wing appears a couple of years later and Suzuki decide that two-strokes have had their day, waste a huge amount of money on the RE-5 rotary, and plan a range of four-strokes instead, saving time by basing them on the Z1. GS550 and GS750 fours duly arrive in 1976. Simultaneously, Kawasaki prove they weren’t content to rest on their laurels by launching the Z650, injecting new life into a shrinking-capacity class. It would probably have been possible to make a 650 engine out of the 900, but they didn’t. Despite a superficial family likeness, the new Zed was all new.

There are a couple of reasons why this might have happened. The Z1 motor used a built-up crankshaft with roller bearings, a bit like the bottom ends of the two strokes that Kawasaki had been associated with in earlier days (and going back further still, the 650 BSA clones inherited from the takeover of Meguro). Built-up cranks are expensive and tend to make a lot of noise, both being characteristics that persuade manufacturers to use a one-piece forging running in plain bearings instead. After a long history of roller bearing singles and twins, Honda had gone the plain bearing route from the beginning on the CB750 and succeeding fours. In many ways the bottom half of the Z650 engine was like the CB500s, with an inverted tooth chain primary drive leading to a crossover gearbox, alternator and ignition on the ends of the crank. The two parted company design-wise at the point where the central cam chain went upstairs. Honda stuck with low-tech sohc right up until the new CB750KZ/9OOFZ series arrived in 1979, but the Z650’s lid included twin cams, just like the Z1.

There are a couple of reasons why this might have happened. The Z1 motor used a built-up crankshaft with roller bearings, a bit like the bottom ends of the two strokes that Kawasaki had been associated with in earlier days (and going back further still, the 650 BSA clones inherited from the takeover of Meguro). Built-up cranks are expensive and tend to make a lot of noise, both being characteristics that persuade manufacturers to use a one-piece forging running in plain bearings instead. After a long history of roller bearing singles and twins, Honda had gone the plain bearing route from the beginning on the CB750 and succeeding fours. In many ways the bottom half of the Z650 engine was like the CB500s, with an inverted tooth chain primary drive leading to a crossover gearbox, alternator and ignition on the ends of the crank. The two parted company design-wise at the point where the central cam chain went upstairs. Honda stuck with low-tech sohc right up until the new CB750KZ/9OOFZ series arrived in 1979, but the Z650’s lid included twin cams, just like the Z1.

Also like the King, the lobes prodded open a pair of valves directly, the difference being in the position of the adjusting shims in relation to the buckets. On the larger engine they were on top, so they could be fished out easily to set the clearances, while on the 650 they were underneath the bucket, which meant the cams had to come out to do the same job. Although this was obviously an extra hassle, in practice the clearances rarely needed adjustment, the advantage being that it was impossible for shims to be spat out, as sometimes happened on over-stressed Z1s.

Also like the King, the lobes prodded open a pair of valves directly, the difference being in the position of the adjusting shims in relation to the buckets. On the larger engine they were on top, so they could be fished out easily to set the clearances, while on the 650 they were underneath the bucket, which meant the cams had to come out to do the same job. Although this was obviously an extra hassle, in practice the clearances rarely needed adjustment, the advantage being that it was impossible for shims to be spat out, as sometimes happened on over-stressed Z1s.

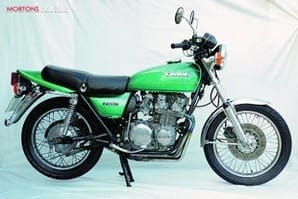

In most other respects the Z650 was like a scaled-down Z900. A steel double-cradle frame housed the engine, with conventional telescopic forks and swingarm suspension. Spoked wheels of the usual 19in front, 18in rear size carried a set of squidgy high-walled tyres that were reckoned to be treacherous in the wet, as per the popular perception of Japanese rubber. A single disc looked after front braking (twin discs were an option), while the rear was an ordinary sls drum.

Opinions were divided about the looks. Standing alongside the new Suzuki GS750 opposition in its metallic green meanie colours, the Z650 looked quite small, dainty and somehow less butch; which it was, being four inches shorter and 40lbs lighter than the GS.

Kawasaki messed around with the Z650 quite a lot in the early years, while keeping the basic engine. The B2 of 1978 was a mild update, the most obvious change being the colour schemes available. Under the skin, the swingarm had proper bearings instead of bushes (a la Suzuki GS), and the cam chain was now automatically tensioned. If you were lucky. The Z650C (Custom) was quite different visually, immediately recognisable by its cast-alloy wheels, twin front discs and silver paint. It looked smart, but as with most late-70s bikes fitted with ‘mag’ wheels made out of heavy chunks of aluminium, this model was probably worse in most ways from a functional point of view. The SR650 (coded D) came in 1979 and was more of a custom bike than the Custom. The main giveaway was the obligatory 16in rear wheel, a regrettable trend started by Kawasaki on the 900LTD. Also of note was an exhaust system that grouped its pipes in such a way that the cylinders helped each other to breathe. It looked odd, but it worked. Although the 650 carried on until 1983, after 1980 it had effectively been replaced by the Z750, which spawned the GPz750 and GT750, not to mention all those smaller fours in 400, 500 and 550cc guises. Few people noticed, but the 650 engine was updated with later technology, including alloy wheels across the range, better brakes, electronic ignition, and 32mm CV carbs instead of 24mm slides. In sympathy with the 750, the kickstarter lever was also deleted.

Kawasaki messed around with the Z650 quite a lot in the early years, while keeping the basic engine. The B2 of 1978 was a mild update, the most obvious change being the colour schemes available. Under the skin, the swingarm had proper bearings instead of bushes (a la Suzuki GS), and the cam chain was now automatically tensioned. If you were lucky. The Z650C (Custom) was quite different visually, immediately recognisable by its cast-alloy wheels, twin front discs and silver paint. It looked smart, but as with most late-70s bikes fitted with ‘mag’ wheels made out of heavy chunks of aluminium, this model was probably worse in most ways from a functional point of view. The SR650 (coded D) came in 1979 and was more of a custom bike than the Custom. The main giveaway was the obligatory 16in rear wheel, a regrettable trend started by Kawasaki on the 900LTD. Also of note was an exhaust system that grouped its pipes in such a way that the cylinders helped each other to breathe. It looked odd, but it worked. Although the 650 carried on until 1983, after 1980 it had effectively been replaced by the Z750, which spawned the GPz750 and GT750, not to mention all those smaller fours in 400, 500 and 550cc guises. Few people noticed, but the 650 engine was updated with later technology, including alloy wheels across the range, better brakes, electronic ignition, and 32mm CV carbs instead of 24mm slides. In sympathy with the 750, the kickstarter lever was also deleted.

Despite the capacity disadvantage, the Kawasaki was almost as fast as the Suzuki GS750, its deadly rival. The 650 made a claimed 64bhp at 8500rpm, only a handful of paper horses down on the GS.

Despite the capacity disadvantage, the Kawasaki was almost as fast as the Suzuki GS750, its deadly rival. The 650 made a claimed 64bhp at 8500rpm, only a handful of paper horses down on the GS.

Depending on which road test you read, both did about 120mph and clocked standing quarters in around 13 seconds. However, there were some unaccountably slow results from Z650s, and I remember a theory going around that Kawasaki had changed something in the engine or carburettors during production of the first B1 model, cutting power. Still, whatever the specification sheets said, the proof of the pudding was in the riding. From the pilot's perch, the Z650 felt nothing like a GS750. Subjectively, the K-bike was faster (unless you got one of those allegedly detuned models, of course), the plain bearing engine having an infinitely smooth, revvy nature. In contrast, the GS felt a bit stodgy and rumbly. The same was true of the handling. Where the long-wheelbase Suzuki was stable to the point of being slow steering, the Kawasaki was much more responsive. Overall, l'd say the Kawasaki was more fun to ride than the Suzuki. If you think I'm biased, let me point out that I owned a GS750 when the Z650 was in its heyday.

As with the Z1, Kawasaki got the design of the 650 right first time in most respects. From the beginning, the engine worked reliably and was simple enough for anyone to fix and maintain with a few basic tools. Ironically, later versions with automatic cam chain tensioners were probably weaker, because it seemed to take many attempts before the mechanism was made dependable. The enemy of any engine with plain bearings is dirty oil, or an interrupted supply, which will wreck everything in seconds. Unfortunately, after 30 years there aren’t many bikes around that have a full service record, so you have to rely on your ears and eyes to spot trouble. Watch and listen for smoke, knocks, rattles and zizzes. Z650s should make a bit a of a whistle, but not much else, although if all four cylinders aren't firing properly the primary drive and clutch will kick up a racket. That noise will go away when the engine is running smoothly. However, worry if it doesn't.

As with the Z1, Kawasaki got the design of the 650 right first time in most respects. From the beginning, the engine worked reliably and was simple enough for anyone to fix and maintain with a few basic tools. Ironically, later versions with automatic cam chain tensioners were probably weaker, because it seemed to take many attempts before the mechanism was made dependable. The enemy of any engine with plain bearings is dirty oil, or an interrupted supply, which will wreck everything in seconds. Unfortunately, after 30 years there aren’t many bikes around that have a full service record, so you have to rely on your ears and eyes to spot trouble. Watch and listen for smoke, knocks, rattles and zizzes. Z650s should make a bit a of a whistle, but not much else, although if all four cylinders aren't firing properly the primary drive and clutch will kick up a racket. That noise will go away when the engine is running smoothly. However, worry if it doesn't.

Even the gearbox, a slightly weak feature of the Z1, is generally good on the 650, but everything wears out eventually, so check for loud whines and/or slipping out of mesh under power or on the overrun. Engines and gearboxes are always fixable, assuming the barrels haven't welded themselves to the studs and you wreck the crankcases trying to prise them apart. If all else fails and originality isn't an issue, parts from other fours in the same family can be used.

Increasingly with older Japanese bikes, the tricky problems are caused by all the bits that were once never given a second thought. When breakers were full of Z650s and other Kawasakis of similar vintage, you had a good chance of finding spares off the shelf. Now that things likes frames, swingarms, wiring looms, mudguards, instruments, wheels, etc, are expiring through old age, you need luck and patience, and possibly plenty of money, because rarity and expense go together like BSAs and oil leaks. ![]()