Kawasaki first proposed a 500cc two stroke triple in the late 1960s, when Japanese manufacturers were making a concerted effort to cater for American tastes in particular. In the US, acceleration was what sold bikes (and cars, for that matter).

The 350 Avenger twin was already as fast as most British 650s but even more power was needed to trounce the opposition completely. Further expansion of the disc-valved twin wasn’t practicable, so more cylinders was the answer. Aircooled fours are prone to overheating whether the cylinders are arranged in a row or a square, but an in-line triple had less of the same problem.

As disc valve induction is really a non-starter when one pot is sandwiched between two others, so Kawasaki used simple piston porting, with the carbs on the back of the barrels rather than outboard of the crank, as on the twins.

There was nothing particularly special about the engine from an engineering point of view (even the British had produced in-line two stroke triples). In fact, the preceding twins were more technically advanced.

Power was taken from a roller-bearing crank to the transmission through a gear primary drive and sent to the back wheel by a five-speed constant mesh gearbox. All very ordinary.

Power was taken from a roller-bearing crank to the transmission through a gear primary drive and sent to the back wheel by a five-speed constant mesh gearbox. All very ordinary.

One slight oddity was the shift pattern – neutral at the bottom and five up – and Kawasaki’s provision for right or left foot change, simply by putting the lever on the relevant splined shaft sticking out of the casings.

For true novelty, you had to look to the ignition system, which used electronic triggers instead of creaky mechanical contact breakers. At least, that’s what most markets had. Here in Britain the GPO was concerned about radio interference, so our triples had to make do with good old points for a time.

Somehow I doubt whether the GPO chaps had much to worry about. Launched in 1969, import numbers were minuscule until Agrati took over, and remained small-scale until Kawasaki UK was established and set up a proper network.

By this stage King Z1 was on the scene and large two strokes were an endangered species, so the H1 and its KH500 offshoot, introduced in 1976, were always rare.

This ensured that few people had ever ridden one, which helped enormously to cultivate the racetrack-derived ‘Green Meanie’ mythology, of course.

After being churned through the rumour mill for a year or two, the popular conception amongst my group of L’s Angels was that Kawasaki H1s were: a) so powerful that it took superhuman strength just to keep hold of the bars; b) so unstable that you were almost certain to fall off on the first corner; c) so thirsty that you needed to fill the tank every thirty miles; d) so hard on spark plugs that they lasted a few minutes, if you were lucky.

Typically, most of this was complete rubbish, which meant that my first ride on an H1 a few years later was really a bit of a let-down. Yes, it was fast, but the world had moved on by then. My arms were still firmly in their sockets, the handling felt like any other bike of the same era and I didn’t need to change a single spark plug.

Petrol did seem to disappear from the tank at a fairly drastic rate, but what do you expect from a large two stroke?

Original is the best!

Although I’d recently ridden Kawasaki 250 and 750 triples, this was my first outing on a 500 for a while. Each engine size has its own particular character (including the often overlooked 350/400 version), but the original just might be the best. The screaming 250 was good fun for a teenager, perhaps a bit too much like hard work for grown-ups. At the other end of the scale, despite being the fastest, 750s seem almost sensible because the sudden step in power had been smoothed out.

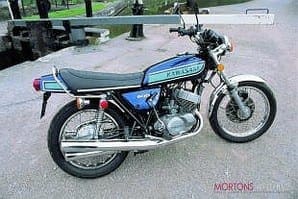

Ah, but the 500, now that’s something else! The test bike was an H1F, a tamer triple than early models. Responding to scurrilous rumours about instability and ‘Kamikaze 500s’, the package had gradually been toned down.

Allegedly, the power band was less knife-edge than before… Oh yes? As I discovered, by modern standards, the engine is still incredibly all-or-nothing. You initially get lulled into a false sense of security, however.

It fires up easily enough, filling the entire parish with blue smoke and the nostalgic aroma of expensive burnt oil. The noise is incredible, a sort of jangling, crackling, whining cacophony of sounds from umpteen different sources.

Once a bit of heat percolates through and the accumulated crankcase gloop has been sent back out of the three chrome pipes, the row subsides and the haze clears. Well, enough to see where you’re going, at least, but following traffic will still cop a lungful. You can only wonder what the pollution level is compared to a modern fuel-injected four stroke with a catalyst!

The five-up gear pattern can be confusing at first, but you soon get used to it once you’ve tried to start off in neutral a few times. At low speed the 500 feels like a quite normal 1970s’ Japanese bike – clutch working smoothly, gears shifting easily, controls all in the usual places…

The engine isn’t exactly enthusiastic about pulling away from low revs but with sensible throttle use, oiled spark plugs just don’t happen. Whack the twistgrip wide open at say, 3000 rpm, and it’ll probably drown, though, which might be when you’re thankful that Kawasaki provided three threaded holes under the seat for a fresh set of NGKs.

You can also cruise along in fifth at 50-60 mph admiring the scenery (assuming no other triples have passed through recently). Ridden in convoy with a Honda step-thru, I’d say there’s a good chance that 50 mpg will be within reach. But really, you don’t want to do that!

You can also cruise along in fifth at 50-60 mph admiring the scenery (assuming no other triples have passed through recently). Ridden in convoy with a Honda step-thru, I’d say there’s a good chance that 50 mpg will be within reach. But really, you don’t want to do that!

What you should do is leave it in second and wait for the engine to hit 6000 rpm at full throttle. Waaaahhhh, go the intakes, accompanied by a crisp exhaust wail. An instant later the tacho is hovering around the red line and the power disappears again, ready for the next gear.

Sixty bhp may not be spectacular nowadays but it’s the way it arrives that makes the H1 so thrilling to ride. You just can’t help grinning and imagining what a shock riders must have had back in 1969.

Into perspective

To put things into perspective, Kawasaki claimed 60 bhp at 7500 rpm for the Mach III. Triumph’s race-bred Daytona 500 was credited with 39 bhp at similar revs. Even the new Trident 750 only managed to produce 59 horsepower while weighing about 100 lbs more.

Kawasaki quoted a standing quarter time of 12.4 seconds. UK road tests achieved something quite close, although by the time the H1F came along, about 14 seconds was more typical. My guess is that it took enormous skill to get the bike off the line quickly. Either it bogged down or the front wheel headed skywards – not entirely normal behaviour back then.

Anyway, this being merry olde England rather than ‘straightaway’ America, sooner or later you have to go round a corner (gulp). Could any bike handle as badly as the myth says? It’s hard to see how: the double-cradle frame looks strong enough, the suspension no better or worse than usual for the era. What could go wrong?

It all depends on what you mean by ‘handling’. At normal public road speeds the H1 steers well enough. The springs and dampers don’t work in perfect harmony but you’re no more likely to take an unscheduled trip through a hedge than you are on a Suzuki GT750, Honda CB750, or similar contemporary. Perhaps the real problem was more to do with the way the triple arrived everywhere going faster than expected and also had the capability to produce sudden bursts of power half way round a corner. The throttle works both ways, as they say, it’s just that on Green Meanies it only has on or off positions.

Obviously, instability was the result, so the poor H1 gained a reputation for being lethal. Exactly the same thing happened when the Z1 upped the performance envelope again in 1973.

All things considered, a 60 bhp 500 two stroke triple is a lot less scary than it was 30 years ago. Even so, the H1 undoubtedly still has charisma and excitement by the shed load, which wasn’t something you got with the identikit fours produced by Japanese manufacturers for the next generation of speed freaks. ![]()